Animal masks workshop

Ann Kristin Klausen, Mats Gøran Dale, Lars Harald Køste Solbakk and Rutt Astri Olsen

Nord Universitet, Nomadic Hub Arctic Art Education

13.05.2025

Narsaq, Greenland

Summary

One of the workshops was held with lower secondary students at the school in Narsaq. The students created masks of Greenlandic animals using recycled materials and watercolour pencils. Together with their teachers, they translated the animal names into several languages. The goal was to use sustainable materials and support place-based learning rooted in the students’ own ecoculture. Although the original plan was to hold an animal parade, there wasn’t enough time, so we took photos instead. Along the way, the students shared personal stories about hunting, traditions, beliefs, and dreams, showing how creative work can open space for reflection and belonging.

As part of a larger interdisciplinary project focused on creativity, identity, and local culture, several workshops were held with students in Narsaq, a small town on the southwest coast of Greenland. These workshops aimed to connect students’ everyday experiences with artistic expression, language, and sustainability.

One of several workshops was held with lower secondary students at the school in Narsaq. In this workshop, students had the opportunity to explore local and familiar Greenlandic animals through artistic and interdisciplinary activities. The main task was to create animal masks, with each student choosing an animal they felt a personal connection to—through their own experiences, family stories, or local traditions.

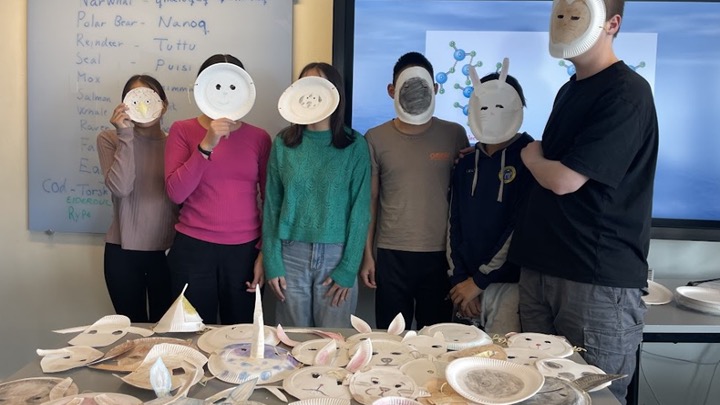

The workshop began with a discussion about animals in the surrounding area, and students were invited to suggest animals they knew and wanted to work with. These included everything from whales and seals to musk oxen, reindeer, ravens, and arctic foxes. Together with their teachers, the students explored the names of these animals in Greenlandic, Danish, and English—and in some cases also in Norwegian. This translation work introduced a natural multilingual element and created space for reflection on language, culture, and belonging.

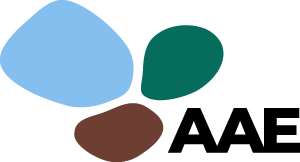

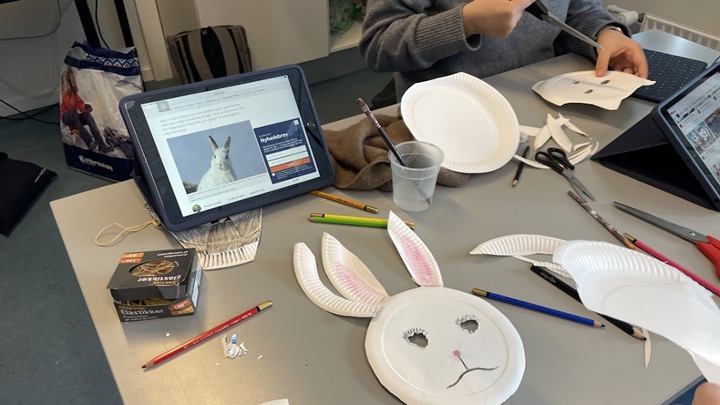

The mask-making process used simple and accessible materials. Students used watercolour pencils to draw animal faces on recycled paper plates, which they then cut and shaped into wearable masks. We emphasised the use of sustainable and reused materials with a minimal climate footprint. While we would have preferred even better material choices, the situation required us to improvise with what was available. With more time, we could have gone out into nature with the students and collected natural materials such as leaves, shells, and feathers. Still, it became an important point to show how creativity and environmental awareness can go hand in hand, even under time pressure.

Local teachers acted as interpreters and educators, improving the workshop’s effectiveness. Students were able to ask questions, such as whether they could use iPads to research animals for their masks.

Originally, the plan was for students to wear their masks and participate in an animal parade to showcase their work. Due to time constraints, we had to adapt and instead took photos of the students wearing their masks. This became a reminder of the importance of being flexible and open to improvisation, especially when working within different cultural and practical frameworks.

Throughout the process, students shared stories, memories, and experiences related to the animals. Many talked about hunting, which remains an important part of Greenlandic culture. Some shared proud moments, such as shooting their first whale or reindeer, while others spoke about beliefs, superstitions, and dreams connected to the animals and the surrounding nature. Thoughts about the future also emerged—about becoming hunters like their parents or about traveling away and eventually returning home. These conversations turned the masks into more than just art projects — they became expressions of identity, belonging, and life stories.

The workshop was therefore not just a creative activity, but also a learning space where nature, culture, and self-expression came together on the students’ own terms.

After all the workshops were completed, the students’ masks were exhibited alongside the results from the other workshops. The exhibition was first shown at the school, and later in the afternoon and evening, it was moved to the local youth club, where everyone in the community was invited to come and see the students’ work. Having their masks displayed in a public setting gave the students a tangible sense of accomplishment and pride, while also strengthening their sense of ownership over the process and the project as a whole.