Text: Mette Gårdvik

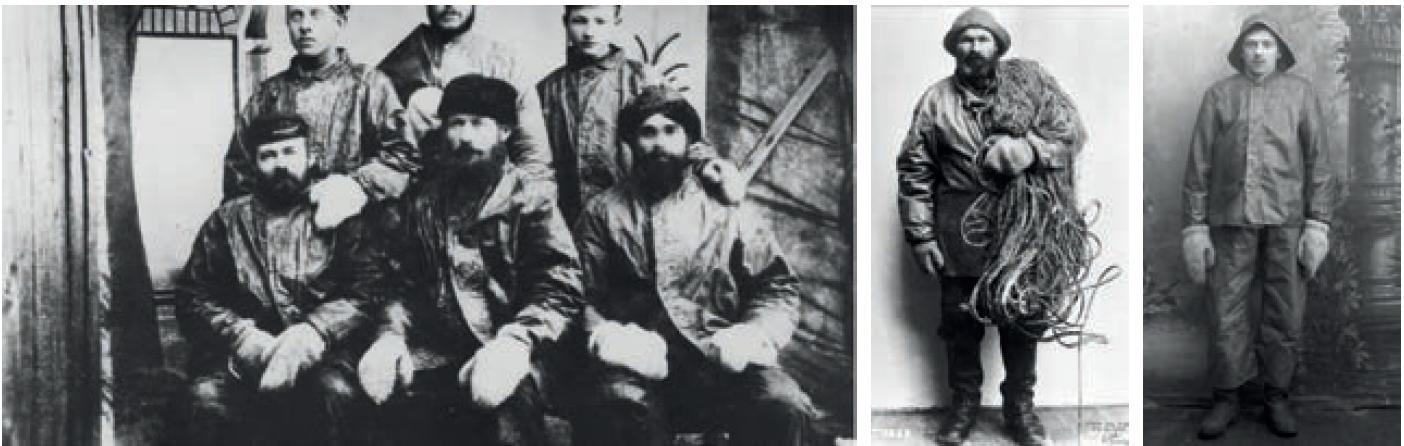

Cover photo: Figure 1. Image 1, 2, 3, series. When fishing in Lofoten, it was common practice to have a portrait of either your crew or yourself. The painted photography backdrops were a standard feature of early photography studios (1860 – 1920). All the fishermen are wearing the special home-made mittens. Photo: Digital Museum

As dwellers in the arctic landscape,

we are all connected through our

memories related to cold hands

and a warming pair of mittens.

Fishermen’s mittens were once one of the most important part of the work attire of fishermen along the Norwegian coast (Figure 1). The mittens were made of wool and protected the hands from the water, cold, fish and tools during the hard work at sea in frigid climates (Figure 2). With its special properties, wool is a unique natural material that is insulating and warm even when it’s wet. Wool from the Old Norwegian Short Tail Landrace sheep breed has good insulating properties and was considered the best wool for the mittens. It consists of soft bottom wool and long, straight coat hair. The long, smooth cover hairs are water-repellent and the garment is strong at the same time as it retains heat. The women produced the mittens from scratch and knew all about the long process of how to feed the sheep and cut and sort the wool before tearing and carding. It was an art to spin the yarn correctly as it should have a long spin and at the same time it should be thick and soft. The mittens were knitted in double size and felted. The mitten maker’s embodied knowledge made them aware of how much the mittens should be felted to be waterproof and not too hard for proper use.

This essay concerns a Community Art (Austin, 2008) project that invited the participants of the spring school 2021, Living in the Landscape (LiLa) to cross borders by the art of knitting a pair of Fishermen’s Mittens. The participants were given an opportunity to wander from the coast of Helgeland, Northern Norway, and into the history of the fishermen’s struggling life through their own contemporary experiences of knitting, felting and making a pair of mittens. As dwellers (Ingold, 1993) in the arctic landscape we are all connected through tradition and our memories related to cold hands and a warming pair of mittens.

The Art of Knitting

At the age of seven, during a recess at school, I watched some older girls knit. I memorised how they used their knitting needles together with the yarn; one needle put under the other, cast on and then pull out the new stitch, repeat. At home I told my mom that I wanted to knit corrugated iron since that’s what the pattern looked like for me and how I thought I could visualize it for her. She didn’t understand at all what I meant but still casted on some stitches and gave me the pair of knitting needles. I have knitted ever since.

For me, knitting is like meeting up with a good old friend, and as an artist and teacher in arts and handicrafts at the university, I always, one way or another, circle around the art of knitting; through my own projects, by teaching students, in discussions with my colleagues/others and in travels. Another aspect is the huge and worldwide knitting community with a continuous amount of ideas, patterns, pieces of yarn or knitted artworks that creates interest. As a dweller on the coast of Helgeland, Northern Norway, my landscape concerns the wellbeing, enjoyment and ownership of a good pair of knitted woollen mittens, and especially the process of making them. The nature, the materials, the technique and the tools, and (for me) the simplicity of making a functional object of only some yarn and knitting needles, creates an holistic approach to my own private taskscape (Ingold, 1993).

The Tradition of Making Fishermen’s Mittens

The Fishermen’s Mittens have several names, and the most common in the local dialect is Sjyvott (sea mittens). Traditionally, it was the housewife’s responsibility to breed “Sjyvottsauen” (the sea mitten’s sheep) and produce the yarn (Lightfoot, 2000) (Figure 3). The sheep were selected because of their long shiny coat hair that is especially suitable for Sjyvott knitting. The cover hairs are combed and then spun by turning the rocker wheel to the right to obtain a rightspun (Z-spun) yarn. Examination of older sea mittens and conversations with older informants have made it known that z-spun yarn is stronger than S-spun for use in sea mittens and other textiles related to sea work.

The mittens became softer and easier to felt when the fat (lanolin) was allowed in and most often they used the yarn unwashed. They were felted to the right size by using a felt board with grooves of wood together with lukewarm water and soap. The mittens were rubbed over the grooves and well felted, but not too much so, because then they became too small and cold. They could also be carded on the inside for better insulation (Klausen, 1998).

The fishermen had to wash their mittens free of fish droppings and dirt after work. They dipped the mittens in the sea, knocked them on a rock and trampled them into the snow, or hung them after the boat. A more special way to clean the mittens was to put the cod’s gallbladder inside the mitten and step on it. When the mittens were rinsed in seawater, they were fine and white again.

When there was a barter, the sea mittens could be used as a means of payment at the land trader. It is said that the captain and the pilot had to wear white mittens. They were easier to see when they waved their hands to give orders. The mittens were used and repaired as long as possible until they were completely worn out. Worn out mittens were not thrown away, but taken home where parts could be used for soles or sewn on pieces of old oil trousers and placed on a bench as a «seat pad».

Constructing an Online Community of Knitters

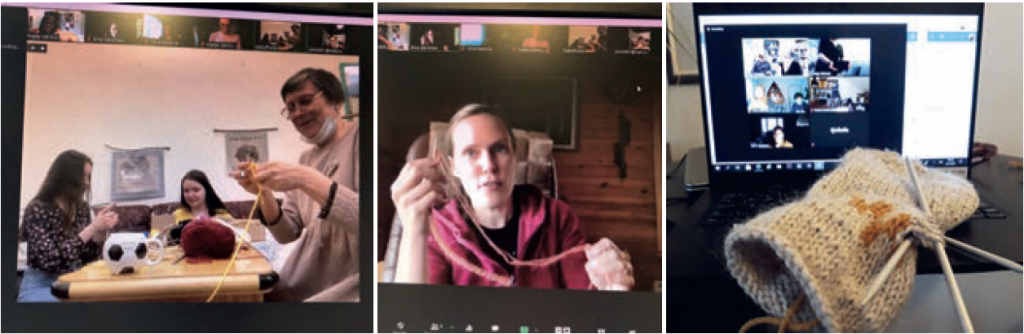

Due to Covid 19 The LiLa School (2021) had to be arranged as an online class, and I gave a lecture about the cultural history of the Fishermen’s Mittens. I responded to questions about the knitting process and gave information about which yarn and needles to use, and three patterns to choose from. It turned out that there was a need for more guidance and I therefore offered two online knitting workshops (Figure 4 & 5). Both events turned out to be a friendly, cozy happening and mutual space of learning with an unformal approach where questions were asked and techniques shared.

Not all participants had skills related to knitting whilst others were professionals. The wide range of skills made an interesting community since knowledge was shared and problems solved by participation from all the participants. We also experienced some challenges with the online event since the camera mirrored a person, or pair of hands, so the knitting turned out reversed. I myself, being left handed, knit right handed, so I had some challenges explaining the different steps of the process.

Some of the participants struggled to choose the right yarn (100% wool, no superwash), which is important for the felting process. The knitting technique was also quite challenging for those who had never tried it or trained enough to be skilled. I also had a hard time guiding both online and in person at the same time. Through my lecture and the workshops, the participants gained insight into the importance of mastering the knitting technique together with knowledge about material qualities and knitting needles. The discussions around the process continued and the feeling of mastery arose along with the production of mittens. Most of the participants made their own pair of mittens, some several more (Figure 6).

Reflections

Through a brief glimpse into the lives of classic Norwegian fishermen and by taking part in the women’s process of making a functional object, a knowledge, a deeper understanding, a feeling of mastery and reflection about living in the artic was achieved. It gave new life to a female tradition and strengthened the relationship and connection to our own history and tradition of craftmanship (Figure 7).

The participants were invited to experience contemporary community art, and a community building project through online meetings in knitting techniques, materials and tools.

The joint space of mutual learning created room for sharing thoughts, personal memories and stories related to a pair of mittens.

As one of the participants wrote to me:

It combines the beauty, the tradition and the contemporary of the Arctic together. We carry them in our hands, affecting our doing in the wintertime which, as you tell us, has been taken into account in making the appropriate mittens for the fishermen. This tactile aspect bridges the virtual distance and makes it possible to transmit and share sensory feelings (Maikki Salmivaara).

References

Austin, J. (2008). Training Community Artists in Scotland. I G. Coutts, & T. Jokela, (red.), Art, community and Environment. Educational Perspectives (s. 175-192). UK: Intellect Books, Bristol.

Klausen, A. K. (1998). I Lofotkista. Nesna Bygdemuseum (1998).

Lightfood, A. (2020). Plan for vern av kystkultur en presentasjon av båtrya. Delrapport til Om kulturvern ved kyst og strand. Nors museumsutvikling 4: 2000. Retrieved from kystkulturhttps://www.nb.no/items/3d03ce6adf2e61d4bd1c8eab6319c410?page=7&searchText=Sj%C3%B8votter

Living in the Landscape (2021). Retrieved from https://storymaps.arcgis. com/stories/345326b826054361a50905c6d92a6b56)

Ingold, T. (1993). The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeology, Vol. 25, No. 2, Conceptions of Time and Ancient Society, pp. 152-174.

Images

Figure 1: Image 1, 2, & 3, series of fishermen at Lofotfisket wearing fishermen’s clothes.

Image 1. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021017935823/batlag-fra-berg-tatt-under-mefjordfiske-i-ca-1895/media?slide=0

Image 2. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021015845150/studioportrett-av-hans-jensen-ifort-oljehyre-royserter-og-med-torskegarn/media?slide=0

Image 3. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021015536192/portrett-mann-i-20-ara-star-sydvest-oljehyre-sjovotter-bildet-er-tatt-pa/media?slide=0

Figure 2: Image 4, 5 & 6, series of Fishermen’s Mittens.

Image 4. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021028550815/votter/media?slide=0

Image 5. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021028507849/vott/media?slide=0

Image 6. Retrieved from https://digitaltmuseum.no/021028545652/vott/media?slide=0

Figure 3: Image 7, 8 & 9, series of wool, women carding, spinning and knitting Fishermen’s Mittens.

Image 7. Photo: Mette Gårdvik

Image 8. & 9. Retrieved from https://docplayer.me/12176205-Sjyvotten-averoy-husflidslag-2015.html

Figure 4: Image 10, 11, 12, series from Online knitting workshop.

Image 10. & 11. Photo: Mette Gårdvik.

Image 12. Photo: Mirja Hiltunen.

Figure 5: Image 13 & 14, series from Online knitting Workshop.

Photo: Mette Gårdvik.

Figure 6: Image 15, 16, 17, series of proud knitters.

Image 15. Photo: Virva Kanerva.

Image 16. Photo: Elina Härkönen.

Image 17. Photo: Mirja Hiltunen.

Figure 7: Image 18. A selection of Fishermen’s Mittens knitted as part of the community art project.