Exploring Snow through Art-based and Scientific Inquiry in Narsaq, Kallaallit Nunaat/ Greenland

Text: Karin Stoll, Mette Gårdvik and Wenche Sørmo, Nord University, Norway

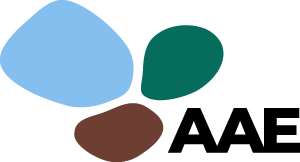

Cover photo: Image 1: Words collected for different kinds of snow in Kalaallit and Norwegian. Photo: Karin Stoll, 2025.

This interdisciplinary workshop was part of the Nomadic hub in Narsaq, Greenland, which consisted of several workshops were the collaborative activities focused on exploring understandings of one’s local environment and culture, while also enabling artistic processes and visual expressions across age groups and generations. The visit offered a unique experience of a Greenlandic school and community for university students, teacher educators and researchers.

All pupils from the seventh to the ninth grades participated in our workshop that used artistic and inquiry-based methods to engage pupils from the local school to explore and express the ecocultural meaning of snow.

In Arctic communities, snow constitutes a natural and self-evident material intrinsically linked to cyclical seasonal changes. The many forms and qualities of snow have direct implications for mobility, hunting, fishing, and other subsistence activities, it gives Arctic people shelter in for example igloos and ice caves. Therefore, snow holds a central place in local systems of knowledge production and transmission. This is clearly reflected in everyday language, where rich vocabularies exist to describe the various types of snow across all Arctic languages.

In the Snow-workshop the Greenlandic pupils were challenged to collect, explore and compare words for different kinds of snow in Kalaallit and Norwegian (Image 1). From a land-based learning perspective, the exploration of snow served as a medium for intergenerational and intercultural knowledge exchange. The rich snow-related vocabulary in Kalaallit, as in other Arctic languages, embodies both physical distinctions and embedded cultural practices, from mobility and safety to seasonal change and environmental interpretation.

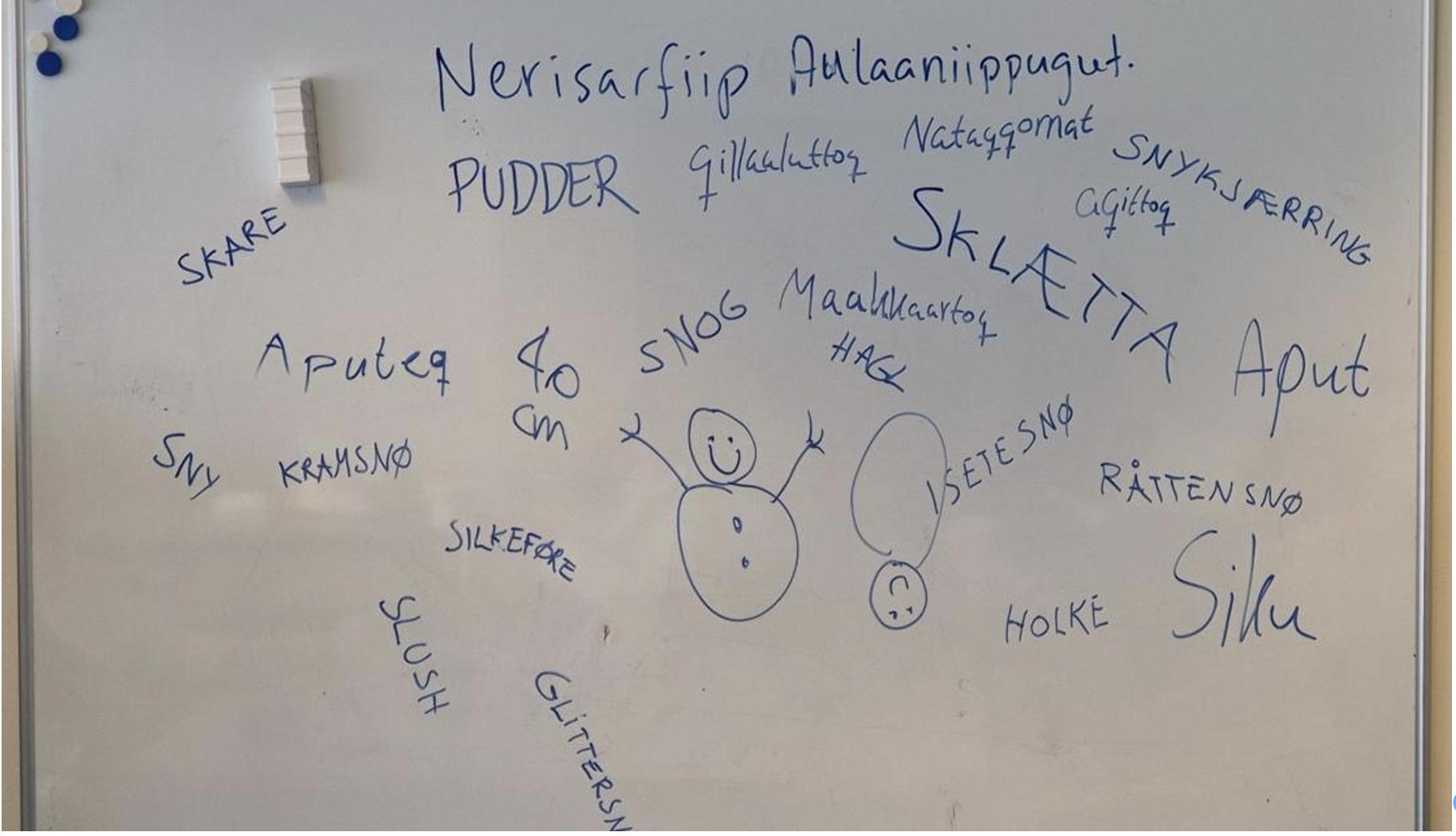

In the art-science integrated workshop the physical and chemical properties of water were discussed and explored. Practical activities helped pupils understand and express their knowledge visually through building models of the structure of snow molecules with toothpicks and candy from the local store (Image 2).

Through cutting hexagonal crystals from paper the pupils reflected on the symmetry of the snowflake. They determined the number of symmetrical axes and the six angles between these. We often see cut out snowflakes in classroom windows with eight or four angles. In these cases, the scientific knowledge of the structure of the snowflake is missing.

During the process the pupils realised why ice crystals take more space than water and could than easily understand why water has a higher density than ice. In this hands-on activity the pupils could also experience that none two snowflakes were alike, like in nature. Together they made an aesthetic expression covering the window of the classroom (Image 3).

In the final task the pupils were challenged to build a village with tiny snowmen. They had to create their own snowman that should express their mood and emotions related to their own homeplace (Image 4). As a member of a group, they had to agree about the placing of the village being visible for the whole community of Narsaq. As local stakeholders the pupils contributed knowledge and stories about the local community’s history and myths.

Art and science were not positioned as opposites. Scientific knowledge is fundamental for understanding environmental systems and materials. Through artistic approaches we tried to foster deep relational awareness and emotional expression related to learning from the land and place.

The workshop also allowed for aesthetic elements such as sensitivity to natural phenomena, human expression, the development and imagination and the ability to play. Not to mention pleasant socializing and everyday aesthetics in an interdisciplinary and international environment. Through artistic and inquiry-based methods, participants engaged with the ecocultural significance of snow, drawing on its multiple forms and meanings within Greenlandic contexts. By integrating artistic processes with experiential learning in the local landscape, the workshop enabled participants to express, reinterpret, and share this culturally situated knowledge, reinforcing the connection between language, environment, and identity.