Text: Peter Berliner and Elena de Casas, Association Siunissaq, Greenland

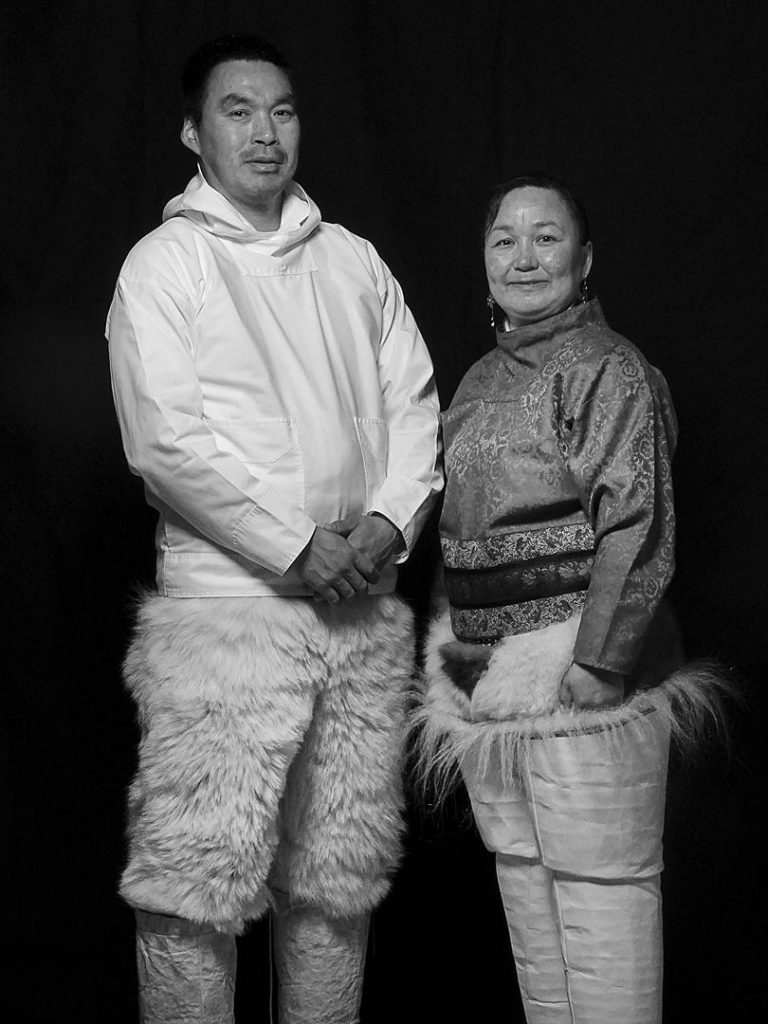

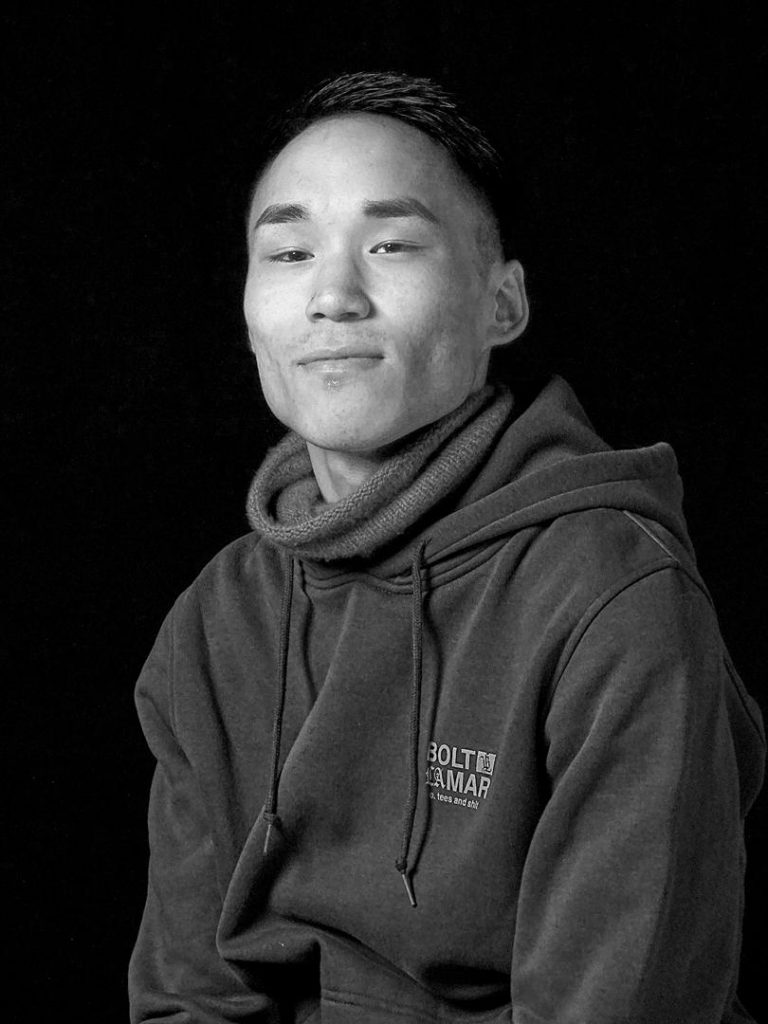

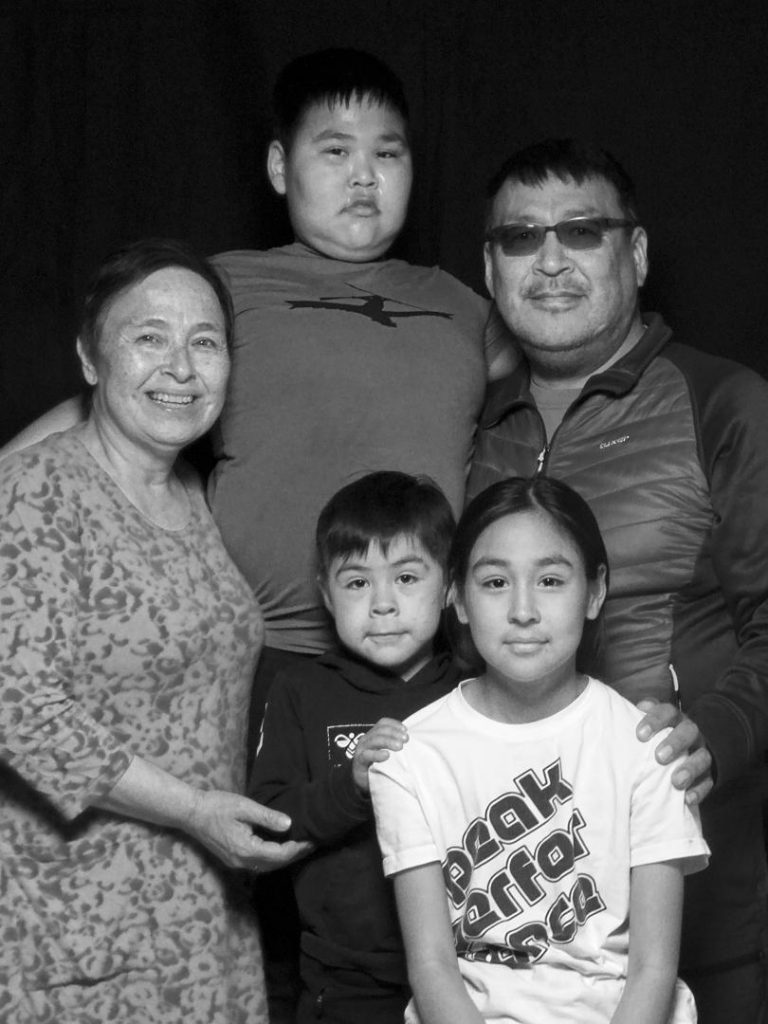

Cover photo: Figure 1. Announcing the community event and exhibition. Photo: participants in the portrait workshop at Majoriaq, Maniitsoq, 2023. Copyright Siunissaq

Siunissaq is an Association that engages in eco-cultural, community-based activities for sustainability. It combines community art and psychosocial activities to overcome social suffering and to contrib- ute to self-determination, social justice, and creativity. We have done that in close and continuous dialogue with the local communities, especially with children, young people, professionals, and the entire local community in the towns Maniitsoq, Tasiilaq, and Nanortalik and the settlements Atammik and Kangerlussuaq. It has been a long journey that has combined psychosocial activities with aesthetic forms of expression, especially photography, but also drawings, movement, music, sculptures, kites and balloons, and installations. We have conducted a series of workshops for young people in the local community as well as for university students and have brought the two groups together. The project works only by invitation of the local communities.

In that framework, we have through more than ten years gradually developed our understanding of what a portrait is and can be. Portraits show us a part of the world, the future, the environment, our culture, and social connections. Portraits are an act, a performance; of the portrayed, of the portrait photographer, of the audience. It is positioning, and it is an action of creating life and art; an action that includes both the position from where we see and the object, i.e., what we see. To see, to gaze, to visualize are actions, and often, it is an action we do jointly, together, at the same time looking at the same. We share the vision.

From Drawing to Photos

The history of portraits in Siunissaq started with drawings. Two by two, the participants in the workshops for students and professionals in education, drew portraits of each other. After finished the drawing, we passed them around in the group and everyone wrote one or more words of appraisal of the portrayed person. Then we put the portraits on the wall and later everyone could bring their own portrait home. This experience evoked emotions of joy, but also of embarrassment as the two people in the team must look, even gaze, intensively at each other. Our inspiration for this activity came from reading an old text on psychotherapy in Inuit lands. Unfortunately, we have not been able to trace the text, but the inspiration lingers on. It mentioned briefly that the arrangements of chairs in psychotherapy there were side by side rather than facing each other. The text explained that as a cultural trait which saw direct and frontal eye contact as impolite and even confrontative. It was better to look at the same view in front of the two chairs and then look at each other occasionally in glimpses. The drawing of the portraits challenged this trait in a both humoristic and intimate way. People laughed heartedly in the process. It also challenged another cultural trait of not pretending to be good at task if you are not sure that you really are good at it. Often, the participants immediately said: “I’m not good at drawing!” And then they did beautiful and expressive portraits, gratefully valued by the portrayed people. Finally, the participants told us that a cultural trait command that people should talk modestly about themselves. Sometimes, they even, with a smile and a grin, said that it is easier to talk badly about other people than to mention them with appreciation. Thus, the final writing on the portraits challenged that by just including appreciative testimonials.

Then we started by using photo portraits instead of the drawing when we did workshops for young people, sometimes adolescents 13 to 14 years of age. Good photo portraits are not easier to do than the drawings, but the time of the process is shorter, even though the young people take twenty-five photos in the process and then pick the best one. Especially in larger groups of young teenagers, the words on the portraits may occasionally disregard the rule of appreciative words. Even though Siunissaq aims to promote freedom of expression, we adhere to the golden rule that one person’s freedom of expression may not limit another person’s rights (and freedom). Hence, we erase these words in full public, in an open dialogue, and without ever mentioning anything about who wrote them. We also erase sexist and other ideologically impacted stigmatizations, in a joyful but still serious manner, with the full participation of the young teenagers entering adolescence with an awareness of citizenship and sexuality.

In the Siunissaq, we also did workshops on the sexual and reproductive rights. The participants made sculptures of people as bodies and drawings of the many genders and the attributes of them. Often it started with stereotypes and ended by writing the same rights and human qualities to all the many gender identities. Both the sculptures and the drawing were a kind of portraits even though they were generalizations. They were portraits of everyone, of us all, as we could recognized ourselves in them.

During the workshops, the young participants made photos of themselves in places, i.e., in environments that invoked emotions, thoughts, and symbolic meaning. Some of the portraits were with hidden faces, by masks or hoodies, or in shadow, in silhouette, or with a light effect that partly made the face unrecognizable. Others were with open faces, but often in an environment, a place, or with a dress or other signs that signalled connectedness to that place in the landscape or in the cityscape or to the culture. These photos portrayed connectedness, they were portraits of connections, of being in, or even belonging, to a place, a symbol, a moment.

Gradually, we developed the idea of the photos of the participants to become portraits rather than just photos. We define a portrait as a (re-)presentation of a person, a group, a family. In the presentation the portrayed is depicted. A portrait holds a likeness of the portrayed, in physical traits, in character, or in symbolic ways.In the many centuries of painted or sculptured portraits, mainly the power elite had means to have portraits made. However, occasionally artists did portraits of poor people, as Van Gogh’s “The Potato Eaters” that captured the physical appearance and conveyed the social circumstances, i.e. the hardship and the social suffering of the portrayed. The development of photographical portraits made the portraits more accessible to people. In visual art, new forms of portraits evolved, such a dadaist, cubist, and surrealist portraits, that used the visual media to present various perspectives simultaneously, including philosophical ideas and social criticism. In the history of photo portraits, the very early social portraits taken by Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson of a fisherfolk community, showed a combination of social engagement and artful portraits. Its many individual and group portraits form, as a collection, an artwork that portrays a community. A community portrait, which shows the social resilience and the human dignity of the community.

Community and Connectedness

Siunissaq developed the idea of connectiveness and community resilience portraits and in 2019, we became partners of a Nordic collaboration, funded by the Art Council Norway and the Arts Foundation Denmark, on art and community. Our contribution was workshops in the town Maniitsoq and the settlement Atammik in Greenland. The young participants in the workshops took portraits of people in the community, produced these portraits, and made exhibitions of the portraits in the centre of the town and of the settlement as public events. The portraits were taken outside, in the streets, in a mobile photo booth with coloured backgrounds, and thus, also a series of public events. The portraits were a collaboration between the young photographers and the portrayed. Often, the portraits became social portraits, as people came to the boot with their family, friends, and colleagues. Also, the individual portraits were social as they were taken in a public event in the street, as they involved collaboration, and as they were taken to be exhibited in a community event. The portrayed and the young photographers collaborated on conveying a message, an impact on the spectator, who also included themselves on the portraits. The message is of human dignity, of attachment and caring for each other, and of engaging the spectator in a deeply felt human encounter. In various contexts around the world, the reactions of the audience include emotions of feeling attached, of feeling involved in a human meeting, and of appreciation of the portrayed people. The portraits are of humanization, of the strength of human beings to reach out to each other, to be in communication, to be together in this life, in the flow of life, and with the ability to care for each other and build a responsible and peaceful world.

Collective Expressions

The portraits are collective aesthetical expressions. they entail a process of creative collaboration and the portraits as the final product. We call it community art as it involves the community in the process of creation. We have described the community event of the exhibition where the same people were in the portraits and were looking at the portraits. It is a double gaze, a seeing and being seen at the same time.

The experience of the connectiveness, community, and social portraits made us consider how portraits can show our engagement in life and in sustainability of our shared world—in the Arctic, in the Nordic context, and globally. We named this idea: “sustainability portraits”, which can be understood as visual representation or depiction of efforts and contributions to sustainable development through engagement and initiatives.

This project cooperates with projects on sustainability portraits in Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

The sustainability portrait project started by making over five hundred portraits of people in Maniitsoq. The portraits were created in a makeshift studio at the Majoriaq school by a group of eight young people, aged 16 to 24 years old. People came to the studio, sometimes one person, but often, two or a family. It was a collaboration between the portrayed and the photographers in the same vein as in the above-mentioned social portraits. We showed the portraits at a community event in Maniitsoq, an exhibition in Nuuk, and later at an exhibition in Bodø in Norway, at a UArctic Conference.

Just as in the reception of the social portraits, the audience, the viewers, expressed that they were emotionally touched by the dignity of the portrayed people and that they, the audience, felt very connected to them, and that they sensed that the portrayed people reached out and made a profound human contact with them. A man from northern Alaska said,

“When I look at the portraits, I really feel at home. You can see that the people in the portraits are looking at someone they know, at the young people who are taking the pictures, and at us. They are not smiling to a stranger, they are smiling to somebody, they know.”

Two young women from Nunavut said when they saw the portraits, “It’s simply like being at home in Nunavut. When we see the faces and their expressions, we can see all the suffering that these people have been through, and we can also see how they maintain their human dignity and beauty. They are like family; it feels like home. Their personalities shine through; everyone is so distinct and beautiful. It is like coming home and being welcomed by the portrayed people.”

Another viewer wrote a comment, “the portraits capture the beauty of the Inuit and connection with family.” Two people from Greenland wrote, “Great portraits, making you smile.

Dialogues

The first author of this text had dialogues with the two visual artists, Tina Enghoff and Soren Zeuth and with the psychologist Elena de Casas, all three founding members of Siunissaq and facilitators of the aesthetic and psychosocial activities and workshops of Siunissaq through more than ten years. Tina and Soeren facilitated the portraits with the young participants. All the portraits are taken by the young people.

Soeren responded to hearing the comments of the audience, “That’s what it’s all about; that people become visible to each other. They show themselves openly to someone they are comfortable with.” That may be why the audience sensed being someone, who the portrayed people felt comfortable with. The audience got positioned as a human being, someone to trust and relate to. The audience become part of the artwork as they respond to being seen as trustworthy people. It is a humanization, which – according to the dictionary – is to make kind and gentle; to position as kind and gentle; to call forward the kindness and gentleness of the audience. This humanization starts in the process of creating the portraits.

Tina says,

That is precisely the core of what we do, namely that you feel at home. You can see that the people have been through suffering, but also that they have retained their human dignity through it. I think that’s beautifully said. And it is linked to that we take the participants seriously as human beings. That is the heart of it; the keyword for us in Siunissaq. To create the portraits together is a wonderful experience for the young people, as we take the portrayed seriously, too. And the audience as it is only successful if others have as much of experience by looking at it as you have of creating it. It’s wonderful when art becomes a collaborative process.

The portraits and humanization fold into each other. The folded process also includes a professional side to photographers and community builders. Tina says, We stand out as a highly qualified and professional team and the young people want to contribute to the team. They listen to and observe the technical aspects of the portrait-taking; where the light comes in, the glare, timing, and all those things. The participants understand that we all are professionally serious, and it makes them participate. It is craftmanship of high quality and thus, as aesthetic expression.

Soeren follows up by saying, “in the series of black and white portraits, we stick to the aesthetic approach and so, it becomes a creative process, an aesthetic expression, yes art, as it wants to tell us something; it is a creation and not just coincidence; there is an idea, an expression in it.” Tina adds, “We chose to do five hundred portraits, not just five, as it opened for a learning process of increasing creativity. 500 portraits give a huge experience and impact.”

Portraits as humanization

Elena reflects on the reception of the portraits as humanization,

The people in the portraits made an attachment to the photographer, like saying, we trust you and we are here with our full presence. You are fully present, and I am, and through our shared presence, we create a portrait that will impact on. other people. It is a shared creation, an aesthetical expression, which is a product of the “eye” of the photographer and the way, the portraited people presented themselves. The young people had an idea before the click of the camera, a vison of what to receive from the others and how to contribute. That is making community. It is a creative expression. They wanted to tell this in the portrait. That is why, at the exhibition in Bodø, people stopped in front of the portraits and wanted to tell us that the portraits touched them, almost as if the portraits were in direct contact with them. The viewer, the audience, told that they felt invited into a community with the portraits. They felt welcomed, like making attachments and connectedness. The audience felt included in making community.

Elena continues by saying,

The audience shared that feeling. It was as if an invisible tread of humanity linked us together as we stood there in front of the portraits, looking into the welcoming eyes of the portrayed as we saw them there through the eyes of the young people in Maniitsoq and now also through our own eyes. The sustainability portraits are a narrative of resistance to a world that dehumanises people. They convey our efforts to build a shared meaning, between us, and give a sense of being alive to all of us. It is humanization as we see human dignity in all of us. The portraits help us to see the other and thus, to change your subjective position. We widen our identity together. It is a process of human understanding, where we can share human dignity, appreciating the human value of us all. It is a creative act, an action.

The sustainability portraits contribute to sustainability through humanization, i.e., to be kind and gentle, to connect to others with care and togetherness.

References

Berliner, P. (2022). Portrætter, fotografi og fællesskab i en grønlandsk kontekst [Portraits, photography, and community in a Greenlandic context]. In M. Fieldseth, H. Hammer Stien, & J. Veiteberg (Eds.). Kunstskapte fellesskap [Art-based communities] (pp. 303–340). Oslo Bokforlaget.

Berliner, P. (2020). Art and Community – a study of art and cohesion. In Research projects at Ilisimatusarfik (pp. 9–11). Ilisimatusarfik, University of Greenland. https://uni.gl/media/6050834/ilisimatusaat-english-2020.pdf