A journey of creating art together with Land and people and, through that, fostering supportive, inspiring and joyful Arctic collaborations for living in harmony with the Land and people.

We hope these guidelines will support you in planning and carrying out sustainable and inspiring new genre AAE projects. The plan also justifies the relevance and significance of your project. The aim is to ensure that all participants and collaborators understand the project’s goals and ways of working and that they share a common vision and language when discussing the intentions and plans of the project.

Elements of an AAE Project Plan

The project plan, prepared at the outset of the process, consolidates all the essential elements of the project, including its intentions, purposes and working methods. The plan also justifies the relevance and significance of the project.

A solid foundation for project planning includes familiarisation with the location, Land, involved communities, community leaders and knowledge-holders and, where necessary, the relevant stakeholders and socio-cultural realities of the region. When international teams design AAE projects, it is common for the mapping of knowledge to be based on various types of publications, including maps, books and museum exhibits. Whenever possible and appropriate, the planning phase includes visits to key locations and meetings with community partners. These interactions, often carried out by the project partner living in the region closest to the local community, provide opportunities for dialogue, helping to clarify wishes, needs and shared objectives.

It is essential to remember that in Arctic contexts, communities – predominantly Indigenous or local communities – are not only stakeholders but also the holders of unique knowledge systems. These systems may guide the project’s ethical, methodological and creative directions. Respect for local leadership and self-determination is a foundational principle of all AAE projects.

A good understanding of the project’s thematic content requires a multidisciplinary approach. This process is similar to research, where prior studies, existing projects and theoretical frameworks provide insight and guidance. The project team shares these learning tasks, agreeing on intermediate deadlines for presenting and gathering findings. Often, the planning phase accounts for up to one-third of the total project workload.

Well-planned and contextually appropriate artistic and educational activity is at the heart of an AAE project, enabling site-specific, situational and phenomenon-based learning.

The project plan should outline the team’s views on learning and art – for example, in terms of equality, inclusion, accessibility and decolonisation – as well as outlining ecological, social and cultural sustainability. The plan also needs to reflect sensitivity towards the Arctic context, including the seasonal rhythms, ecological constraints, Indigenous and Northern knowledge systems and the lived realities of local communities. Recognising the ongoing impacts of colonial histories and extractive industries in the Arctic is essential for ensuring that the project avoids cultural appropriation and promotes ethical collaboration.

These guidelines are published in:

Jokela, T., Huhmarniemi, M. & Hiltunen, M. (2025). Project design for new genre Arctic art and art education. In M. Huhmarniemi & T. Jokela (Eds.), Living with Land and people: A handbook for artistic project and art-based action research in the Arctic (pp. 20–29). University of Lapland.

THE PROJECT TITLE

The title should clearly and concisely capture the nature and idea of the project, making it easy to refer to in communication. If necessary, an acronym or abbreviation may also be created.

WHAT IS THE MAIN IDEA AND PURPOSE?

Summarise the project’s main idea and purpose: what will be done, with whom, when and where?

THE SCHEDULE

Plan and outline the timeline: when does the project start and end, and what are the intermediate milestones by which certain sub-goals should be achieved?

THE TEAM

List the members of the project team and outline possible areas of responsibility. For example, responsibilities for documentation or communications may be assigned to specific team members.

WITH WHOM?

Identify the organisations and individuals involved in the project and describe their roles. Name experts, supporters or funders and clarify their contributions and interests. It is essential to clearly outline the goals, expectations and motivations of all partners.

AAE activities should involve Elders, artists, craft makers, cultural leaders and local organisations to ensure that the lessons learned reflect community values and addresses significant issues, such as climate change, land rights and cultural preservation. Preliminary knowledge of Northern ecoculture and material traditions should be ensured in collaboration with knowledge holders. This approach fosters active citizenship, strengthens cultural identity and facilitates the transfer of knowledge between generations, ultimately supporting a sustainability transformation.

WHERE?

Describe the location(s) where the project will take place. Justify the choice of location, considering its opportunities and potential challenges. Will the project – or parts of it – be conducted online or remotely?

Consider using public spaces and natural surroundings as learning environments. In the North and the Arctic, the Land itself is an essential part of cultural identity and learning. AAE can take place in natural settings – such as forests, riverbanks, coastal areas, tundra and mountains – where participants can learn traditional ways of life and cultural practices through first-hand experience alongside art-based environmental studies. Community centres, cultural festivals and other public events can also serve as dynamic learning spaces that blend traditional and contemporary art and knowledge, reinforcing a sense of place and belonging.

WHY?

Justify the project’s relevance from both community, environmental and Arctic perspectives. Explain why this project is meaningful for the development of AAE, Arctic sustainability and your personal and professional growth. The rationale should address a specific challenge that the project responds to or a vision of the new possibilities it opens up. Consider how the project acknowledges and supports the cultural sovereignty of Arctic peoples and communities and how it contributes to the decolonisation of knowledge, practices and representations.

It is essential to integrate social and cultural considerations into AAE activities. The North and the Arctic face social, environmental and cultural challenges, including the impacts of climate change, cultural erosion and the exploitation of natural resources. Therefore, AAE should address the urgent issues related to local and Indigenous rights, cultural diversity and sustainability. Addressing these topics can foster a deeper understanding of the complexities of life in the Arctic while raising awareness of social justice and environmental issues.

GOALS

Define a central goal: what kind of impact does the project aim to achieve? This may involve revitalising cultural heritage, animating ecocultural traditions, empowering communities and making public artworks. Goals might also include supporting intergenerational knowledge transfer, honouring storytelling traditions or fostering respectful relationships with the Land. If you work with people, consider the community’s visions for their future, not just the project team’s assumptions. You may also set sub-goals related to knowledge, skills, attitudes and social learning. Generating discussion and public awareness may also be one of the aims. Goals should be realistic and concrete. If the AAE project is carried out at school, the curriculum may guide goal setting; in community projects, goals should be shaped through dialogue with the community.

It is important to involve local stakeholders, Indigenous representatives, cultural representatives and Elders in both the planning and implementation phases of AAE. This ensures that the AAE aligns with the community’s cultural values, ecocultural traditions, needs and customs. It is crucial to prioritise co-design in which the community actively participates in shaping the AAE project plan and objectives, leading to a more authentic and meaningful experience for all participants.

MEANS AND WORKING PRACTICES

Describe the practical methods to be used: what will be done, and how? Careful planning of the methods, working practices and content increases flexibility in practice.

In Arctic projects, the methods may also need to be adjusted to local seasonal conditions (e.g. light, weather, migration patterns) and cultural protocols (e.g. times for community gatherings or ceremonies). Participatory and co-creative approaches are often recommended to ensure that the community’s voice shapes not only the outcomes but also the process itself. In larger projects, the methods may be organised into so-called work packages to break the project into manageable parts.

AAE combines traditional Northern knowledge and material culture with contemporary art practices. The practice may include traditional art forms – such as carving, weaving and storytelling – as entry points to explore cultural values and ecocultural traditions. Local artists and craftspeople can be engaged as part-time instructors, enabling students to learn directly from community-based knowledge holders. This approach supports cultural preservation and revitalisation while recognising local expertise. Outdoor activities, place-specific art and collaborative projects with local residents are central, encouraging direct engagement with the Land, water, plants, animals and seasonal rhythms through art-based methods. Digital tools and online activities can be applied to AAE projects.

THE THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Briefly describe the key theories related to art and learning that inform the project and introduce the relevant concepts. Justify the project idea and working methods by referencing previous Arctic art projects and relevant research in AAE.

Read more about the theoretical background below.

THE PLAN FOR EXPLORING THE PLACE AND SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT

A variety of methods can be employed to explore the chosen location and its ecocultural context, including multisensory observation, site-specific artistic activities, interviews and digital tools. In the framework of AAE projects, the notion of community is understood broadly, encompassing human inhabitants and more-than-human beings, environments and material agencies. Read more about this phase below.

THE EXPECTED RESULTS AND IMPACTS

Evaluate the potential results and impacts of the project as an extension of its goals. Consider why this project is important. In art education, especially in rural Arctic communities, outcomes are often more qualitative than quantitative. Reflect on the anticipated effects on participants, the local community and the environment. The project’s impact may extend beyond its immediate scope, influencing future activities or perceptions of Arctic art and AAE.

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to increasing the accessibility and impact of the project’s actions and outcomes. A communication plan outlines guidelines for both external communications and internal interaction, including outlining the principles for creating a safer space. The team should agree on communication practices, such as channels and meeting schedules. Some communication targets local communities and stakeholders, while other communication addresses broader audiences via media platforms. Specify who should communicate what, to whom and when. Use appropriate tools and media.

Read more on communication in the guidelines below.

BUDGET AND FUNDING PLAN

Outline the project’s anticipated costs and available resources. List the facilities, equipment and tools available to you.

SUSTAINABILITY

Reflect on the sustainability dimensions of the project. Does the project contribute to sustainability transformations, and does it have an impact on social or cultural sustainability? Is the project carried out sustainably, limiting the ecological footprint and avoiding harm to nature?

THE EXPECTED RESULTS AND IMPACTS

Evaluate the potential results and impacts of the project as an extension of its goals. Consider why this project is important. In art education, especially in rural Arctic communities, outcomes are often more qualitative than quantitative. Reflect on the anticipated effects on participants, the local community and the environment. The project’s impact may extend beyond its immediate scope, influencing future activities or perceptions of Arctic art and AAE.

PROJECT ETHICS AND GIVING CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethics in art and art education projects are closely tied to the project’s goals, methods and relationships. Ethical practice encompasses how artists or educators plan and execute their work, engage with participants and acknowledge authorship. This includes reflecting on power dynamics, inclusion and responsibilities in both privileged and marginalised contexts. In AAE projects, it is essential to clarify roles and consent. If a project is intended to be evaluated and presented in a research context, ethical practice includes defining the anonymity and role of participants. This is especially important when working with vulnerable individuals, who must be offered anonymity if they wish. From the beginning, participants should be informed about whether they are involved as named artists, credited contributors or anonymous participants.

When working with Northern and Arctic (often multicultural and/or Indigenous) communities, it is always important to respect cultural protocols and sensitivities. It is essential to respect local customs, cultural protocols and the significance of any potential sacred sites or practices. It is crucial to ensure that artistic activities are culturally appropriate and do not distort or exploit Indigenous traditions. Ethically, it is also important to ensure that all documentation (e.g. photos, videos and artworks) is done with permission and used respectfully.

A SAFER SPACE

AAE practices should foster inclusive and safe environments where participants can express personal experiences, emotions and social concerns through artistic means. These projects can be viewed as performative situations that invite diverse forms of participation and facilitate dialogue aimed at healing and strengthening community resilience. While sustainability is a global concern, art-based engagement with these issues can also promote individual mental well-being by offering meaningful channels for self-expression and social reflection. This is particularly relevant in Arctic communities where art can play a significant role in addressing mental health challenges – often linked to the impacts of colonial histories – and in supporting emotional and cultural recovery.

DOCUMENTATION PLAN

Who is responsible for documentation? What will be documented, how and for what purpose? Confirm if there is consent for photography, video and potential research use. Formal agreements may be necessary if materials are to be published. Think about the kind of materials to produce: will there be a publication, an exhibition, an online presentation or social media content? This will guide what is recorded and when.

Read more about photo and video documentation below.

Take a Closer Look at the Stages of Project Planning and Action

May these guidelines encourage you to create art education projects that are meaningful, decolonial and sustainable.

These guidelines are published in:

Jokela, T., Huhmarniemi, M. & Hiltunen, M. (2025).Take a closer look at the stages of project planning and action. In M. Huhmarniemi & T. Jokela (Eds.), Living with Land and people: A handbook for artistic project and art-based action research in the Arctic (pp. 30–51). University of Lapland.

Explore the Socio-Cultural and Ecocultural Context

In the framework of AAE projects, the notion of community is understood broadly, encompassing human inhabitants and more-than-human beings, environments and material agencies. This approach encourages considering how humans, more-than-humans and their surroundings co-shape and influence one another within ecocultures.

If physical presence at the location is not possible in the initial phases, remote and digital methods can be used creatively, such as engaging with local social media groups or conducting online participatory mapping. The project plan should clearly describe the chosen methods, intended participants (humans and/or more-than-humans), schedule and forms for presenting the results. Outcomes may take various formats, including text, images, video works, installations or web platforms.

Preliminary exploration is crucial as it helps articulate the project’s relevance and refine its scope. In ecocultural and community-based projects, meaningful directions often emerge from dialogue and attentive intra-action with the local context, including the landscapes, ecosystems, species and human actors involved. Therefore, sensitivity to place and an openness to unexpected forms of interaction are essential for responsible and responsive project design.

Learning from Earlier Art and Art Education Projects

When planning an AAE project, it is essential to engage with what has come before. This means familiarising oneself with earlier projects, artworks and pedagogical initiatives that have addressed similar themes, places or communities. Such contextual awareness honours the work and knowledge of previous artists, educators and community members, and it helps to both extract lessons learned and build upon existing relationships, methodologies and narratives.

Researching local and regional art histories – including Indigenous artistic traditions and other Northern artistic traditions, land-based practices and past community art projects – can reveal important cultural meanings, symbols or protocols related to the place or topic. It also allows for respectful continuation of art and education rather than disruption. In Arctic communities, where histories are often transmitted orally or through lived practice, this process may involve direct conversations with Elders, Northern knowledge holders, artists and educators in addition to studying published materials.

Situating a new project within a broader landscape of past and ongoing work fosters continuity and dialogue across time. It supports ethical practice and helps ensure that projects contribute meaningfully to existing cultural ecosystems rather than appropriating or isolating them. This also strengthens the project’s relevance, resonance and potential for impact, both locally and more broadly, when fostering the impactfullness of art and art education.

Decolonial Research as a Foundation for AAE Projects

It is essential to engage with research literature specifically grounded in Arctic art and art education. Such literature provides culturally and environmentally relevant perspectives that reflect the unique conditions, values and worldviews of Arctic communities. Relying solely on global or mainstream art and art education sources would risk overlooking or misrepresenting these specific contexts. By reading Arctic scholarship, you will gain a deeper understanding of local practices and knowledge systems and contribute to the decolonisation of research and education by valuing regionally rooted ways of knowing, making, teaching and researching.

Concepts and literature worth visiting include the following: Arctic art and design practices, land-based education, decolonisation, eco-cultural resilience and community-based art education frameworks. Relevant authors may include Indigenous Arctic scholars, Northern cultural theorists and artists whose work emerges from the specific contexts of the Circumpolar North. Incorporating such theoretical grounding helps the project to resist extractive or outsider-driven perspectives and instead supports place-sensitive, culturally sustaining and ethically grounded artistic and educational practices.

The book series Relate North has been published annually since 2014 to identify and share contemporary and innovative practices in teaching, learning, research and knowledge exchange in the fields of arts, design and visual culture education in the North.

Education in the North is a journal that publishes research findings, comments and critiques on all aspects of education. This includes formal and informal educational settings, as well as compulsory, community, further or higher education and allied professions (such as psychology, social work and librarianship).

The key literature on the concepts of new genre Arctic art and new genre AAE includes the following:

- Ruotsalainen, J. (2024). Discursive frameworks of Arctic art. Arctic Yearbook 2024 – Arctic relations: Transformations, legacies and futures. https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2024/2024-scholarly-papers/526-discursive-frameworks-of-arctic-art

- Hiltunen, M & Korsström-Magga (Forthcoming). Nomadic antlers. New genre Arctic art education and activism. In A. Sohns (Eds.), Artistic dialogues with the Arctic North: Environmental change and identity in transition. Routledge.

- Jokela, T., Berliner, P., & Manninen, A. (2024). Introduction: Creating sustainability portraits in the Arctic. In T. Jokela, P. Berliner, & A. Manninen (Eds.), Creating Arctic sustainability portraits (pp. 8–12). Lapin yliopisto. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe20241209100493

- Jokela, T., Manninen, A., & Berliner, P. (2024). Introduction: a journey with new genre Arctic art. In T. Jokela, A. Manninen, & P. Berliner (Eds.), Mapping the New Genre Arctic Art Education (pp. 8-13). Lapin yliopisto. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2024120599888

- Jokela T. & Hiltunen M. (2024). New genre Arctic art education as a way of knowing with the North. In T. Jokela T., M. Huhmarniemi & K. Burnett (Eds.), Relate North: New genre Arctic art education beyond borders. (pp. 12–37). InSEA Publications.

- Jokela, T. & Huhmarniemi, M. (2022). Arctic art education in changing nature and culture. Education in the North, 29(2), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.26203/55f2-1c04

- Jokela, T., Huhmarniemi, M., Beer, R. & Soloviova, A. (2021). Mapping new genre Arctic art. In L. Heininen; H. Exner-Pirot & J. Barnes (eds.), Arctic Yearbook 2021: Defining and mapping sovereignties, policies and perceptions. Arctic Portal. https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2021/2021-scholarly-papers/400-mapping-new-genre-arctic-art

Documenting AAE Projects

In the context of AAE, documentation plays an essential role as a tool for learning, reflection, motivation and representing process and artistic productions. In remote and culturally rich northern contexts, documentation becomes both a pedagogical approach and an ethical responsibility. Recording participants’ voices, questions and reflections – alongside visual documentation – helps to make transformations, interconections and artistic growth visible. In AAE, documentation should honour the unique knowledge systems, languages and environmental relationships of Arctic communities.

Documentation and evaluation should create lasting benefits that go beyond the duration of a single project. These may include educational resources for schools, materials supporting cultural heritage preservation, archives for community memory and tools for designing future initiatives. When documenting art and art education in Arctic contexts, it is essential to respect the seasonal rhythms, Indigenous knowledge systems and the interconnection of Land and community.

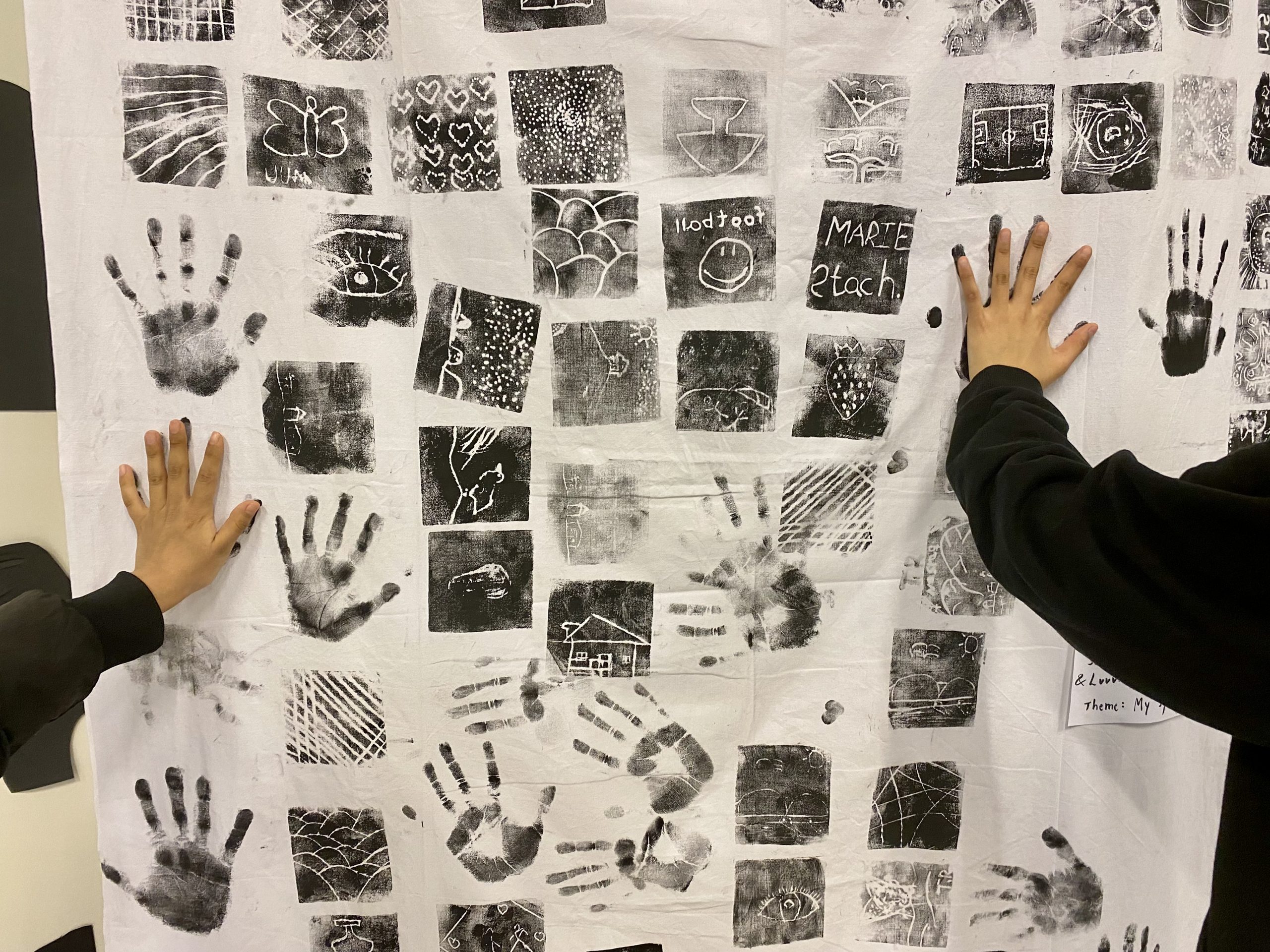

In every AAE project, it is necessary to consider how the documentation represents the core of art and art education. Does it primarily present the artworks as finished objects, or does it highlight artistic, communal and transformative processes? Does it reflect the spirit, cultural context and social environment of the place in which the art was created? In many AAE projects, documentation is often the primary means by which wider audiences can experience the artwork. Projects may take place in remote locations or natural landscapes that are difficult to access, and many artworks are ephemeral, existing only for a short time and experienced by a small group of participants. Thus, documentation is not merely supplementary, it is central to extending the work’s reach, honouring its context and preserving its connection to place, culture and community memory.

Documentation must always be guided by the project’s purpose, goals and theoretical framework. In AAE, art is often understood as a process deeply related to Land and people. Therefore, documentation should emphasise this evolving and relational nature – one that resists extractive or colonial ways of seeing.

Communicating about an AAE Project

In Arctic contexts, communication must be designed with special attention to linguistic, cultural and geographical considerations. Local and Indigenous languages may play a crucial role in ensuring that messages are accessible and meaningful to community members. Whenever possible, consider producing key communication materials (such as posters, invitations or project summaries) in local languages alongside national or international languages.

Involving community representatives or knowledge holders in shaping the communication content can improve cultural relevance and appropriateness. This is especially important when communicating about sensitive cultural topics or local knowledge.

In the North, physical distances and digital connectivity may shape communication choices. Not all Arctic regions have stable or affordable internet access; therefore, traditional and place-based media (such as community radio, village noticeboards and word-of-mouth promotion via local events) remain valuable tools.

When sharing outcomes externally – such as in exhibitions or publications – ensure that you acknowledge and, where appropriate, obtain consent from community partners whose voices, images or knowledge are featured. This helps to uphold the principles of ethical collaboration, cultural safety and co-authorship.

Consider how the results will be shared after the project ends, for example, in exhibitions, online galleries, publications or seminars. Artworks and events live on in various forms, including articles, documentation and memories. Thoughtful communication planning can extend the project’s influence to broader discussions about the role and significance of art and art education. Thoughtful communication planning also contributes to the project’s decolonising potential by ensuring that the community’s perspectives, stories and interpretations are represented authentically and not overshadowed by outsider narratives. When possible, community members should be invited to co-present the results, artworks or findings, whether in local exhibitions or international forums. Creating and exhibiting artworks are important for initiating dialogue. Sharing artworks online with other groups adds a new dimension to the dialogue and allows new audiences to interact with the works.

Also, leverage the channels of partner organisations and the university to reach relevant audiences. The social media platforms of the ASAD network are offered to expand the communication in the Arctic art and design education networks. You can tag the Instagram account @asad_network (as a collaborator of your post) and the Facebook account @ArcticSustainableArtsAndDesign or share in the Arctic Sustainable Arts & Design Facebook group.

Celebrating the Results of the Project in AAE

An AAE project culminates in a meaningful closing phase. As the work progresses, participants often become increasingly committed to the process. Seeing a community contribution – whether material, symbolic or conceptual – can evoke feelings of cultural pride and inspiration. In successful projects with well-crafted outcomes, participants often experience joy, empowerment, increased capability and a sense of belonging. Through the unveiling of the final artwork, they may literally or symbolically have their voices heard and recognised.

In the university context, students are expected to not only celebrate the learning process, their and others’ contributions, and the project’s overall progress, artistic quality and social impact, they are also expected to critically reflect on theme. In AAE, this includes reflecting on how local realities, Arctic ecologies, Indigenous or community-based knowledge systems and collaborative dynamics shaped the artistic and educational outcomes.

Within the pedagogical model of project-based learning, this final phase is often referred to as a ‘closure moment’. It includes evaluation, shared reflection, and giving and receiving feedback. This process helps clarify and give meaning to experiences that may only become fully visible and understandable in hindsight, when the creative and collaborative journey can be viewed as a whole.

The goal of an AAE project – and the way its quality and effectiveness are measured – often extends beyond the institutional setting. Art seeks to be seen, felt and shared. In Arctic regions, final presentations or celebrations are shaped by the nature of the project, the community’s cultural practices and the participants’ wishes. These may take the form of artwork unveilings, exhibitions, seminar presentations, public conversations with artistic interventions, seasonal gatherings, village festivals or other local events.

Such events might welcome families, local residents, community leaders, Elders, knowledge keepers and other relevant audiences. When shared publicly, the value of the artwork increases in the eyes of its creators, and the moment of celebration can strengthen community bonds and the shared experiences of success and recognition.

Media – including local newspapers, radio and social platforms – can be powerful tools for appreciating and amplifying the project. Through increased media visibility, Arctic art and design projects can gain broader recognition and contribute to public discourse on the role of art in sustaining cultures, ecosystems and traditional ways of life in the North.