Text and photos: Antti Stöckell

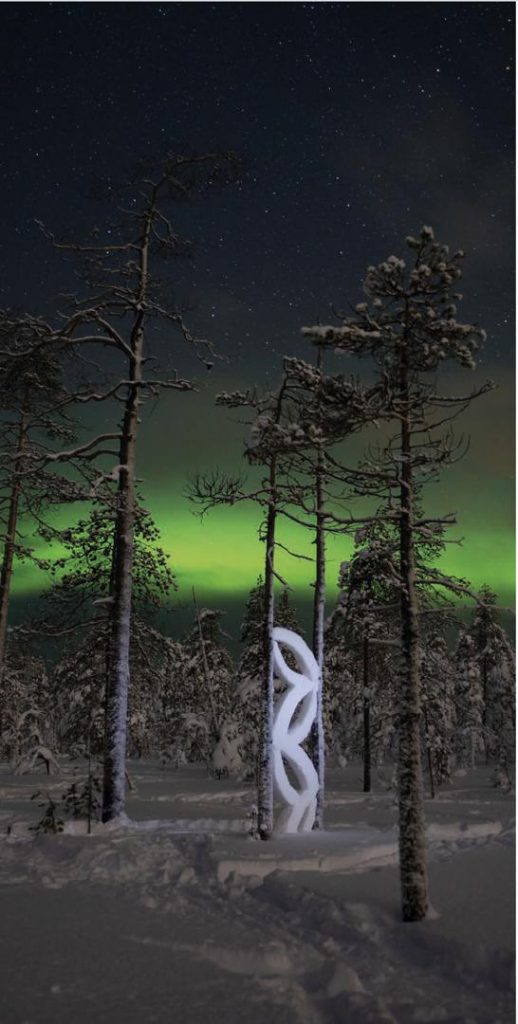

Cover photo: The first snow is always an equally incredible experience; it feels new and wonderful after even dozens of similar experiences. After the middle of October 2020, the first snow of autumn-winter rained with the wind, frosting the tree trunks to be patterned by the artist. For the northern folk, snow makes the winter sensible. Thermal winter begins when the average daily temperature remains below zero.

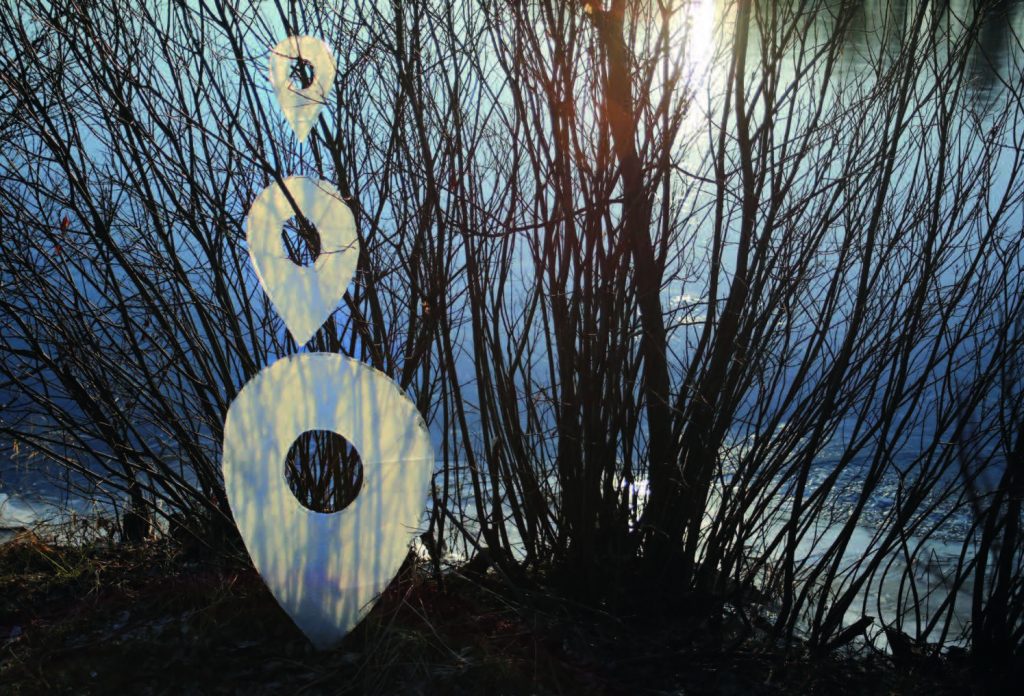

My work of art at the spring online school exhibition, Living in the Landscape, introduces in the form of a video the snow installations in my hometown’s scenery that I made during skiing trips in winter 2020–2021. In this text, I examine my work through three interrelated aspects: winter as a natural scientific phenomenon, winter’s aesthetic, and winter as an activity environment. The artworks of the Snow Games series thus serve as art-based material I bring into dialogue with the natural scientific, aesthetic, and active aspects of winter. I have organised and directed winter art workshops at the University of Lapland for fifteen years. In the workshops, groups of students create large-scale snow sculptures and atmospheres based on moulding techniques, often for schools and villages, or create the interiors for snow hotels with reliefs and ice sculpting. My personal artistic practice with snow differs significantly from these workshops. I primarily work alone, seizing the opportunities of the moment and the circumstances while looking for new chances to create art in winter landscapes. My artistic experience also diversifies my teaching in the field of winter art. My goal is to inspire more and more people in the fields of art education and applied art to discover the richness and opportunities of snow and winter.

WHEN THE TEMPERATURE

DECREASES BELOW ZERO —

THE NATURAL SCIENCE OF WINTER

From a scientific point of view, winter is precisely defined. It has its duration, temperature, amount of snow and depth of frost. Winter is part of a broader phenomenon. According to Vasness (2019), the part of the Earth where the temperature drops below zero and water freezes is called the cryosphere.

About 35 per cent of the Earth’s surface is such an area, half of which takes place as land and the other half as water. Glaciers covered in permafrost occupy less than 11 per cent of that land area. If all the ice in Greenland melted, the seawater would rise by seven meters. The melting of Antarctic ice would raise the seawater surface by 56 meters. The melting of sea ice in glaciers and polar regions has become a symbol of some kind for climate change. In recent years, the increased melting of permafrost has received increasing attention as well. As the frost melts, the ground may collapse and avalanche. There is also concern about global warming via the release of carbon from permafrost into the atmosphere and its further warming-accelerating effects. (Vassnes 2019.)

The snow cover in the northern hemisphere is the cryosphere’s fastest-changing aspect in the natural annual cycle (Vassnes, 2019). The total mass of snow in the northern hemisphere has not decreased, but it rains now more in certain areas, while elsewhere, the mass of snow decreases (Pulliainen et al., 2020). Vasness notes that the whiteness of the cryosphere plays a significant role in climate change. Albedo ( “whiteness” in Latin) is the name of a scale expressing how much a surface reflects the sun’s radiation. On a scale, 1 indicates complete reflection. New, clean snow gets closest to it, with its albedo being 0.8 to 0.9. The light-reflecting property of snow and ice also means that heat is reflected into space. The shrinkage of the cryosphere, especially in the northern hemisphere, thus means a faster rise in temperature in the north, as snow-free land absorbs more solar heat than snow-covered land (Vassnes, 2019).

The millennia-long adaptation of plants and animals to winter is put under severe test when the winter’s climate changes rapidly. The timing of snow cover’s entry and exit and fluctuations in snow cover quality as extreme weather events increase pose serious challenges to many species’ reproduction, protection, foraging and predation (Heikkinen et al., 2020; Haataja, 2018).

Where snow and ice exist, species adapted to frost come to life with wild force as the snow recedes in the spring. The melting and freezing that occur with the natural alteration between summer and winter regulate the water cycle in a life-friendly way (Vassnes, 2019). The cryosphere is evidently in constant change and motion. Global warming, accelerated by human activity, is further accelerating changes in, e.g., sea currents, glaciers, snow cover and vegetation, which in turn are followed by unpredictable changes in a bigger system.

The global scale of the cryosphere is observable in satellite images as expanding and contracting white areas in the rhythm of changes in water states. Alongside the broader picture, we can look at microscopically small phenomena: the crystallization of water molecules into ice, the formation of crystals into flakes and the accumulation of flakes into a snow cover that further changes its nature from a fluffy, airy, earth-protective mass to denser forms, all the way to clear ice. As extreme weather events increase, variations in winter conditions will also bring more significant variation to snow quality in midwinter. After the January rainfall, I have found the surface of a frozen crust to be workable with a saw. On the other hand, an increase in the snow’s amount and density in the north may also mean that snow’s melting could be delayed until May. The expansion of the working opportunities for an artist working with snow is a contradictory experience—I seize the opportunity with joy while I worry about the causes and consequences of the change. An art educator, applied artist or entrepreneur who views winter as a learning environment as well as a field of experiences and services cannot ignore the difficult and painful issues of the changing cryosphere. They have to reflect on their work’s value base and the different traces it produces on the winter landscape and mental landscapes of people. What kind of carbon foot- print does the action leave, and what about the aesthetic footprint?

STUNNING LIGHT, SHIMMERING COLDNESS — THE AESTHETICS OF WINTER

When examining the aesthetic aspect of winter, emphasize the phenomena perceptible to the human senses and the wintry experiences they form. What does winter look, feel and sound like? In the visuals of winter, the quantity and quality of light are crucial. In winter, there is less light, which in turn is offset by the richly light-reflecting properties of numerous states of snow. In the absence of snow, darkness, on the other hand, is prominent. Nonetheless, in winter, the tints of artificial illumination also called light pollution are also emphasized. In addition to light, another highlighted aesthetic dimension is the coldness of winter that we feel on our skin and breathe in the form of the frozen air. In terms of touch, it is interesting that we avoid touching winter other than on the skin of our face while protecting our bodies and hands with thick winter clothes and gloves. The snow worker and the person who moves on the snow feel in their bodies the snow’s essence and quality as a resistor, with friction and weight changing according to nature’s circumstances—from extreme lightness to undesired heaviness. Another aesthetic dimension closely related to the cold is winter’s sound atmosphere. We can hear the frost slamming in the trees and creaking under our steps. The sounds of a river or lake freezing, as well as the sound of ice melting, are some of the most stunning winter soundscapes. However, to a large extent, the winter soundscape in nature is characterized by silence when water, trees, insects and birds are quiet. The sounds of winter are the sounds of action and movement on the snow.

I get to work with snow in a bodily, multisensory way in the middle of this ever-changing and living winter landscape—nature, which Jokela (2015) describes when looking at his own winter art as the basic principle of being flowing through substances and experiences. I join that flow with my art by slightly guiding it, but the artwork soon disappears and is carried away by the flow when it comes to snow. The most permanent marks the work leaves on its author and the audience whom documentaries reach.

When we admire the dialogue between light and shadow in the footsteps we leave on the snow, an increasing number of us are concerned about the global footprint that humanity, as a way of life, leaves on the climate and thus on winter. Alongside my admiration for winter, there has inevitably appeared a slight anxiety about its future. We strive only for what we value and love. It is therefore essential to encourage more generations to discover the beauty of winter and snow.

WORK, DELIGHTS, AND GAMES—WINTER CULTURE

For many people, winter is a season that one must merely survive, while for others, winter means many opportunities to live with its conditions. Vassnes (2019) describes Earth’s early history, back a billion years, when the first living organisms adapted and survived the ice ages by forming symbiotic relationships and collaborating (Vasness, 2019). This is still the case today — we can ally with winter and, of course, work together as communities to survive through the winter.

Traditionally, wintertime has included a wide range of winter fishing and hunting as well as chores and work done under favourable conditions. Ingold (1993) writes about the cycles of natural phenomena with which we resonate in seasonal chores. This resonation creates a taskscape, a landscape from which to-dos and their stages can be found (Ingold, 1993). Traces in the snow reveal travellers and actions immediately, as new rains and the melting of snow fade the traces. Mostly, traces of reindeer herding and forestry work can be found in the forests and swamps where I do my work. Due to the frost that protects the soil, deforestation is carried out in winter. In the forest, there are still winter roads that are impassable during the summer. They are passageways through which the logs can be removed by the snow freezing during the winter’s frost. Spring snow crust provided before and still provides the best conditions for moving and transporting loads in nature. This is how I executed my artistic work in the past, always utilizing as many different weather conditions as possible for ideal snow crust. Since then, I have consciously sought out and developed the new ways I now present to resonate with different circumstances to create winter art. Thus, the wait for late winter has changed to almost constant vigilance and monitoring of the progress of winter.

Wintertime also prominently includes winter delights. A few times, I have detached from my family on a ski slope for a moment and dug a snow saw from a backpack. We experimented with a local mountain biking guide and entrepreneur to combine artmaking along a winter biking trail with promising experiences in March.

Close to the delights is play. Winter games in snow and darkness have fascinated children from one generation to another, and knowledge and skills related to winter and snow have also been learned through play (Nyman, 2004). This is also the case with my own work—after all, I have named the series and the winter-to-winter-lasting unity Snow Games. Jokela (2018) describes contemporary site-specific art as connected to people’s everyday activities, events, and places that, in art education affected by contemporary art, means emphasizing process-like and interactive activities related to technical skills, tools, and methods of expression.

Making art gives me a great reason to move repeatedly in the winter landscape. My equipment, skis, a shovel, a saw, and some random builder tools, such as a trowel, are effortless. Technical skills and methods of expression are shaped and developed under the conditions of snow and winter, deepening into their natural scientific, aesthetic and cultural essence. My work as an artist is a play by which my relationship with nature and the living environment lives and enriches. Simultaneously, I work on my concern for the future of winter in the grip of climate change.

References

Haataja, A. (2018). Pohjoinen. Jälkemme maailman laidalla. Tammi.

Heikkinen, V., Koskimies, P., Manninen, J., & Varesvuo, M. (2020). Katoava talvi. Pohjoisen eläimet ilmaston muuttuessa. Otava.

Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174.

Jokela, T. (2015). Talvi arktisen taiteen ja muotoilun luonnonvarana. Acta Lapponica Fenniae, 26, 41–57.

Jokela, T. (2018). Suhteessa talveen. In P. Granö; M. Hiltunen & T. Jokela (Eds.), Suhteessa maailmaan: ympäristöt oppimisen avaajina (pp. 53–81). Lapland University Press.

Nyman, H. (2004). Leikkimielellä ja lumella / Playfulness and snow. In M. Huhmarniemi, T. Jokela & S. Vuorjoki (Eds.), Talven tuntemus: Puheenvuoroja talvesta ja talvitaiteesta / Sence of winter: Statements on winter and winter art (pp. 40–49). Lapland University Press.

Pulliainen, J., Luojus, K., Derksen, C., Mudryk, L., Lemmetyinen, J., Salminen, M., Ikonen, J., Takala, M., Cohen, J., Smolander, T. & Norberg, J. (2020). Patterns and trends of northern hemisphere snow mass from 1980 to 2018. Nature Volume 581, 294–298.

Vassnes, B. (2019). Pakkasen valtakunta: Kryosfääri ja elämä. Sitruuna kustannus