Text: Elsbeth Bembom & Randy Bruin

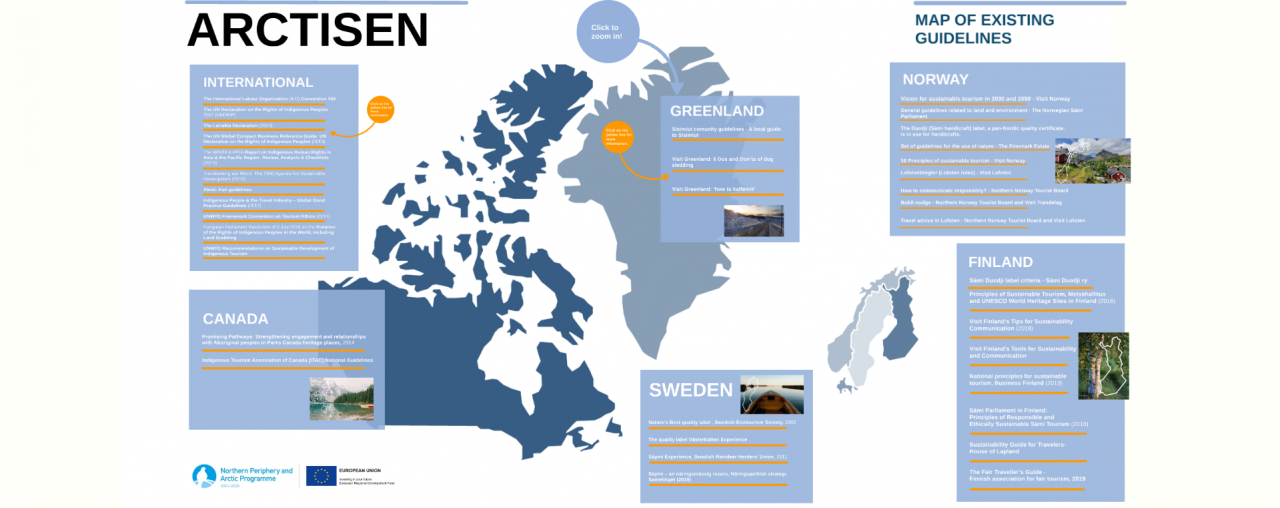

As explored in the previous blog post on Arctic tourism and the Covid-19 pandemic, tourism entrepreneurs and local DMOs have had to rethink their products and marketing strategies to adapt to a growing staycation market as a consequence of the pandemic. This blog post zooms in on issues of cultural sensitivity in this context of tourism during the pandemic. What stories about local culture and everyday life are told to the domestic visitors and how are local communities coping with this different form of tourism development?

During the summer of 2020, Greenland and the Nordic Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden and Finland saw an unprecedented growth of domestic tourists, as traveling internationally was hindered by global travel restrictions. This blog post looks at the implications of the pandemic on culturally sensitive tourism development in the Arctic. We specifically look at the dissemination of local and Indigenous culture to domestic tourists and the general consequences for local communities of the recent drastic changes in tourism. To explore these topics, we listen to the experiences of local tourism experts and entrepreneurs in Greenland, Norway, Sweden and Finland to learn about cultural sensitivity during a pandemic in the Arctic.

Panorama view from Skulsfjord, Kvaløya, Troms og Finnmark, Northern Norway – Photo by M. Blom

Telling other stories?

Whereas the main narrative in tourism marketing targeted at international tourists often revolves around stories that represent the Arctic as an ‘untouched wilderness’, the interviewed experts at local DMOs agreed that a different message was needed for the domestic market. Among international tourists, there is a growing interest in learning about local Arctic ways of living, but many of the domestic tourists want to experience ‘difference’ as well. As Jesper Schrøder, destination manager at Arctic Circle Business, explains: “It’s hard to sell Greenland to Greenlanders, because we sell who we are, and Greenlanders are already that”.

As a consequence, Anette Grønkjær Lings, chairman of Visit Greenland, noted that the staycation market in Greenland demonstrated no interest in stories related to local culture or history, as “digging much more into that […] would be very artificial”. For instance, stories about the national dress or myths around the northern lights became irrelevant. Instead, emphasizing local trademarks, such as national parks, ice caps, fjords and UNESCO sites, became one of the main stories which tourism entrepreneurs and DMOs used to communicate with the domestic market.

“It’s hard to sell Greenland to Greenlanders, because we sell who we are, and Greenlanders are already that” – Jesper Schrøder

Encountering new visitor dynamics

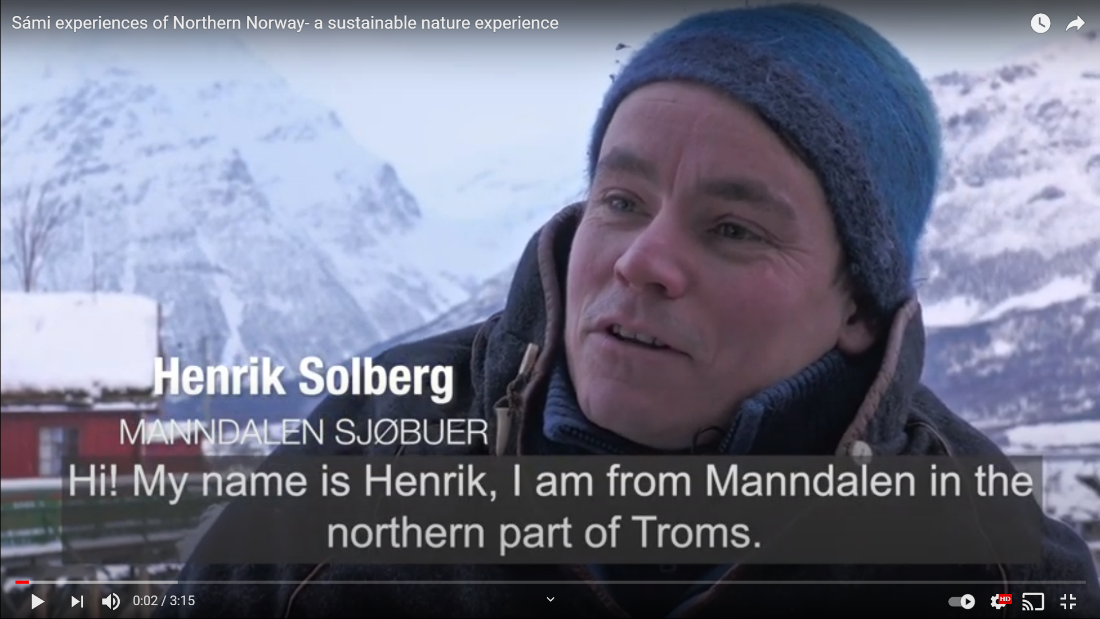

The stories told to domestic tourists were in some way also more detailed. According to Hilde Bjørkli, head of competence and development at Northern Norway Tourist Board, Norwegian tourists “don’t need this kind of surface stories. They need more, more deeper stories”, as they already know Norway. Despite this promising observation, the local experts were less positive when discussing the opportunities for Sámi tourism within the Scandinavian staycation market. Many believed it to be “awkward” or “odd” to visit a Sámi family as a fellow Norwegian, Swede or Finn.

Yet, interviewed Sámi entrepreneurs from Northern Norway told us different stories about their encounter with domestic guests. One of them described that she found it easier to connect with the Norwegian visitors, as they were able to make a deeper connection based on all the stories they had in common as fellow-Norwegians. As the owner elaborates, “they know lots of things about Sámi culture, they have read about it. So, in one way we can tell them the true story”. Another Sámi tourism entrepreneur pointed to how new, domestic audiences challenge usual stories of nature relations: “Norwegian people do not like me saying that we have another way to relate to nature. Because […] they have an identity that they are the outdoor [enthusiasts]”. These examples indicate that new host-guest encounters foster new conversations – not only about national and cultural identities, but also of how hosts and guests engage with and represent their relations with nature in different ways depending on the audience.

Gamme in Skardalen, Kåfjord, Troms og Finnmark, Northern Norway – Photo by R. Bruin

In Greenland, culture is usually not offered as a tourism experience in the same explicit way as in the Nordics as indicated in the above. Yet, other culturally sensitive issues arose when Greenlandic domestic tourists wished to experience a tour with a Greenlandic, rather than a foreign guide. As Salik Hard, senior project manager at Sermersooq Business, explains: “For local habitants, we don’t want to be guided by a foreigner that has been in our culture a few weeks”. As also previously uncovered in an ARCTISEN report, the tourism industry in Greenland depends on foreign workforce, often from Denmark. This issue became even more controversial as a result of the staycation trend and tour operators who were able to offer Greenlandic guides gained a major advantage.

When looking at the staycation boom through the lens of cultural sensitivity, a positive outcome is that it became clear that local stories are best shared by locals. At the same time, the demand for local representation touches upon a complex postcolonial history between Greenland and Denmark as well as upon general challenges of attracting domestic workers in labour-intensive seasonal industries such as tourism.

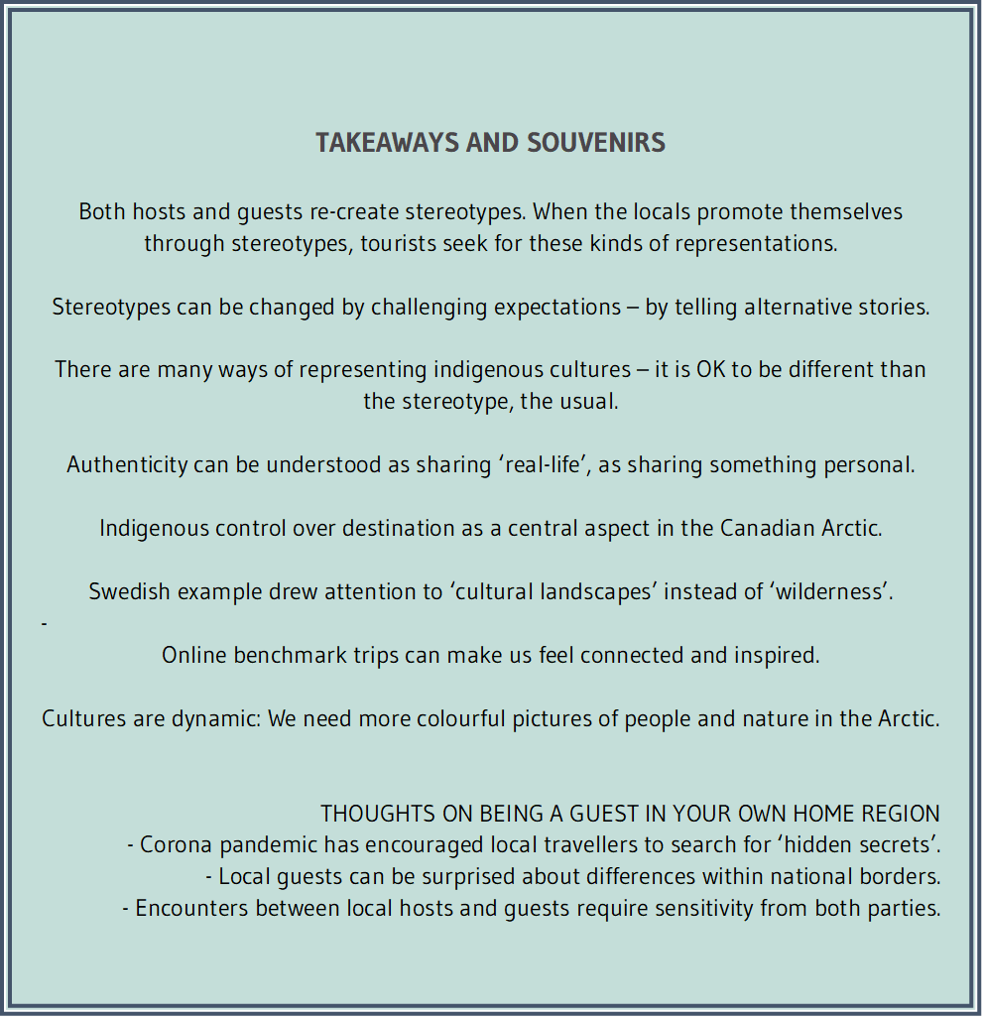

The pandemic as driver of change

The renewed focus on the staycation market has meant that local communities have become even more important. Despite the increasing flows of domestic tourists, businesses in and outside the tourism sector have still suffered. In other words, tourism development is not detached but highly connected to all layers in society, which became clear in our conversations with tourism actors in Finland, Greenland, northern Norway, and Sweden. Even though many differences exist between and within the countries, this is one thing that we can state for most Arctic tourism destinations. As argued by several tourism entrepreneurs, “the tourist industry is an important business. And if we leave, there will be a missing link in the society”. Salik Hard stressed that “the accommodation facilities, restaurants, the tour operators, stakeholders, cultural institutions, (..), are very dependent on the tourism. Absolutely”.

“The tourist industry is an important business. And if we leave, there will be a missing link in the society” – Arctic tourism entrepreneur

Prior to Covid-19, the tourism businesses contributed to local communities in terms of income generation, but also collaborations between businesses within similar and among different sectors. Among most Sámi entrepreneurs in northern Norway, thinking about the society and future generations is part of the business culture according to Solveig Ballo, CEO, and Antje Schlecht, project manager at the Sapmi Business Garden. Both emphasized that economic diversification, or the “several legs to stand on”, is a “society strength” that “actually saved the businesses” from bankruptcy.

In general, tourism entrepreneurs explained their attempt to through their business “show the people that they have to stop and breathe. We have to stop and think.” And how they “hope guests can connect themselves to nature, and (..) will find peace and rest a bit when they are at the camp”. These aims are reflected on their own way of living, as Jesper Schrøder argued: “tourist entrepreneurs are able to have a [satisfying] way of life (..), [by] being out in nature(..)”.

Recent developments have raised fears among tourism actors. Kristian Sievers, project manager at the Regional Council of Lapland, northern Finland, shared that businesses not directly related to the tourism industry are still very connected to tourism companies and when the latter run out of income, the companies providing services for the tourist industry will soon follow. A loss of local participation in his view will also entail the loss of contemporary cultural representation in Arctic tourism experiences. For the nearby future, a northern Norwegian entrepreneur foresaw that many businesses will be bankrupt, take on new jobs, and might not return to the tourism industry.

What will this entail for cultural sensitivity?

(Stay tuned for the article that will look more into tourism dynamics in times of the pandemic in both Greenland and northern Norway!)

Moving on

Our interviews show that despite the crisis situation, domestic tourism has provided an opportunity for tourism entrepreneurs to rethink and reinvent their stories. Also, domestic tourists have had a positive experience (re)discovering and learning about their own country in new ways. These tourism encounters offered new kinds of interactions and in some ways, a deeper connection was made. However, covid-19 hit the Arctic tourism industry hard, which led to bankruptcies, loss of jobs, and the closing of restaurants, shops and other facilities in and outside the tourism sector.

While the situation looks difficult for many communities that depend on international tourism, the staycation growth created an opportunity (although forced) to rethink the stories of the destination and of its cultures.

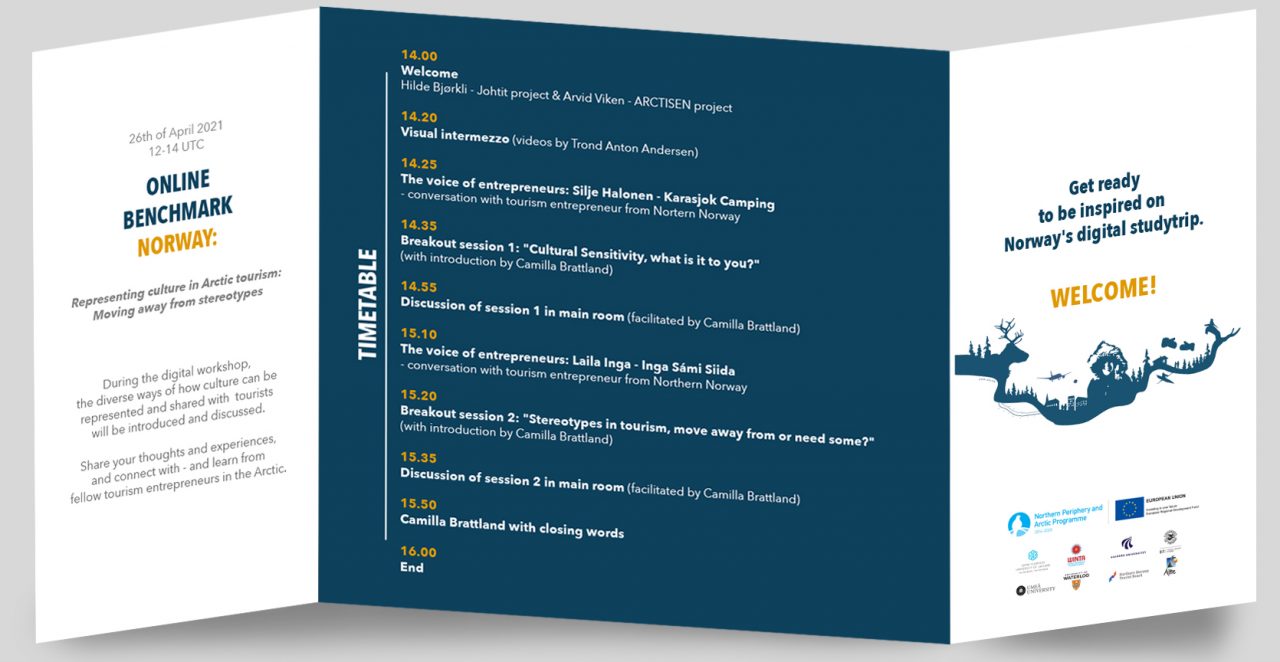

The event brought together participants in

The event brought together participants in