A blog post on Eleonora Alariesto’s (2021) research: ‘The conflict of sacred and contaminant: The impurifying effects of tourism in Sámi sacred sites’

by Elsbeth Bembom & Randy Bruin

Tourism is one of the fastest growing industries in Sápmi and this growth has led to increased negative environmental impacts, such as soil erosion and pollution. Tourism has also left its traces on Sámi sacred sites, such as Ukko’s rock in Finland, which grew into a tourism destination over the years. What happens with the sacredness of the sites, when more and more tourists visit them?

Ukko’s rock, Äijih, in Inari Sámi, at Lake Inari (See photo) is a Sámi sacred site that served for centuries as a sacrificial place and up until this day the rock still remains a place of high significance among local Inari Sámi communities. However, the rock full of meaning has also become a popular tourism spot during the last couple of decades. After a critical opinion piece by Eeva Harlin and Inka Musta on the need to preserve the sacred natural formation (Harlin and Musta, 2019), a local tour operator decided to end landing on Ukko’s rock and the local authorities removed all infrastructure, such as stairs and a dock, that was added to the island. Eleonora Alariesto, from the University of Lapland, inspired her research on this particular opinion piece (Alariesto, 2021), and examined the different forms of contaminants appearing at the Ukko’s rock sacred site using the theory of impurities. This blog post discusses Alariesto’s research through a culturally sensitive tourism lens: How can cultural sensitivity in Arctic tourism contribute to protecting sacred Sámi sites?

Ukko’s rock (Äijih, Ukonkivi, Ukko, Ukonsaari). Photo: Kaisu Raasakka/Ninara/Flickr

A dirty rock?

Even though the increasing tourism activities at this sacred site have positive economic effects for local tour operators and communities, local Sámi people have raised concerns in terms of the negative cultural and environmental impacts on the rock. To explore these sentiments, Alariesto (2021) chose to collect knowledge from news articles instead of interviewing people from the Inari Sámi community, as she did not want to bother them with yet another interview. Her theoretical framework is based on the theory of impurities by Douglas (2000), which means that what is considered dirty depends on local contexts, beliefs, norms and cultural values. Moreover, something is perceived as ‘dirty’ or inappropriate in relation to a host object, which is meant to be protected and kept clean. In her research, she found three forms of contaminants that threaten the purity and the spiritual meanings and values of Ukko’s rock:

- Physical contaminants

Visitors who leave trash behind, urinate, vandalize and harm the nature of the rock are examples of physical contaminants that interfere with the sacred meanings attached by Sámi communities. Other physical adjustments on the island, such as the dock and the stairs, can also be perceived as contaminants.

2. Social contaminants

The Inari Sámi usually do not visit the rock, which makes the presence of tourists and other visitors a source of contaminant that differs from its ‘original’ state. Besides, inappropriate behavior, such as drinking alcohol and snacking at the sacred site, are seen as disrespectful to the spiritual value of the cultural heritage site.

3. Cultural contaminants

Tourists visiting the island have started their own new rituals that are not connected to Sámi spirituality, such as leaving coins behind as a sacrificial practice, like many tourists do at other famous tourism spots (read throwing coins in the Trevi fountain in Rome).

As a result of these contaminants, Alariesto (2021), as a Sámi herself, advocates that Indigenous rights and cultural heritage should be protected, as many aspects of Sámi culture have nearly entirely disappeared after assimilation policies and current conflicts over land-use, where indigenous and capitalist interests clash. As Alariesto (2021) argues: “Furthermore, when protecting sacred sites, it is important to ensure the right of locals to use the sacred site, as these sites are still the subject of a wide range of activities. Sacred places provide a cultural connection with Sámi ancestors, and even if there are no longer active sacrificial rituals there, they are respected and considered essential to building Sámi identity”.

How to move forward in developing tourism at sacred sites in Sápmi? Whether some stakeholders might believe that a ban should be imposed on landing the rock, Harlin and Musta (2019) argue for “better information and guidance, so tourists would know how to act respectfully at sacred sieidi sites”. And Alariesto (2021) believes that: “When Sámi cultures are the major element of a tourism business, cultural sensitivity should be included in its methods of performing its tourism activities” (Alariesto, 2021), which is a thought we aim to discuss further.

“When Sámi cultures are the major element of a tourism business, cultural sensitivity should be included in its methods of performing its tourism activities” (Alariesto, 2021)

Call for future culturally sensitive tourism development

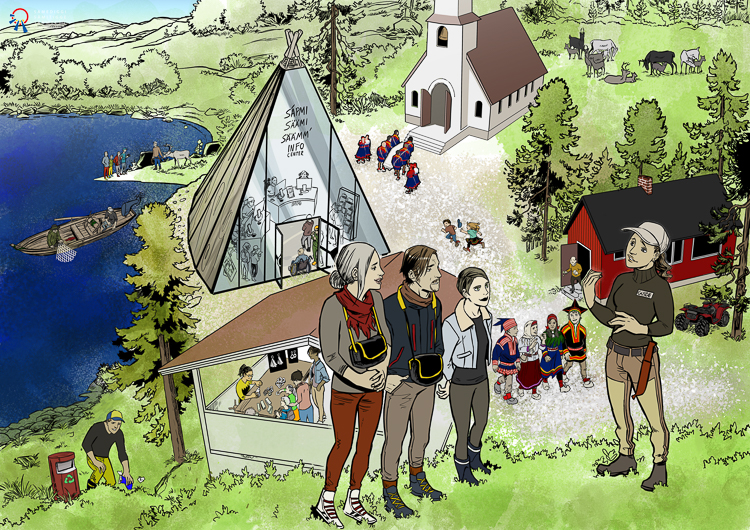

As we have seen throughout the past years during the ARCTISEN project in Sápmi, there is a need for continuous renegotiation over the use of land, which Eleneora’s article exemplifies. In our conversations with Arctic tourism entrepreneurs, local tour operators and DMO representatives, we have heard about examples where tour operators planned to use the forest for their huski safari or snowmobile tours, while Sámi (tourism) businesses have routes for reindeer herding in the same area. Similar to the context of Ukko’s rock, where the needs of Sámi communities, tourists and businesses can create friction, we call for the importance of including cultural sensitivity in tourism development. When tourism stakeholders, whether Indigenous, local or any other affiliation, meet differences with respect, while simultaneously recognizing different needs and knowledge systems through continuous dialogue, disrespectful and environmentally and culturally pollutive behaviour could be avoided. As Viken, Höckert and Grimwood (2021) argue: “… we suggest that culturally sensitive tourism processes occur and thrive in encounters that enable reciprocal exchange between hosts and guests through sharing and receiving, (un)learning and teaching”.

“Instead, we suggest that culturally sensitive tourism processes occur and thrive in encounters that enable reciprocal exchange between hosts and guests through sharing and receiving, (un)learning and teaching” (Viken, Höckert & Grimwood, 2021)

Promoting culturally sensitive tourism practices could serve as a tool to reduce negative cultural and environmental impacts or – as Alariesto (2021) described it: “the impurifying effects of tourism in Sámi sacred sites” (Alariesto, 2021). A call for (more) cultural knowledge, respect, recognition, reciprocity* – in other words, cultural sensitivity – among tourism actors, from tourists to DMOs, could help solve the conflicts of sacred and contaminated sacred sites.

Thank you Eleonora for this inspiring and important research!

Sources

Alariesto, E. (2021). The conflict of sacred and contaminant: The impurifying effects of tourism in Sámi sacred sites. Matkailututkimus, 17(1), 64-70.

Harlin and Musta (2019). Myös Suomessa tulee kunnioittaa alkuperäiskansan pyhiä paikkoja. Accessed on 10th of September from: https://www.hs.fi/mielipide/art-2000006287430.html

Viken, A., Höckert, E., & Grimwood, B. S. (2021). Cultural sensitivity: Engaging difference in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103223.

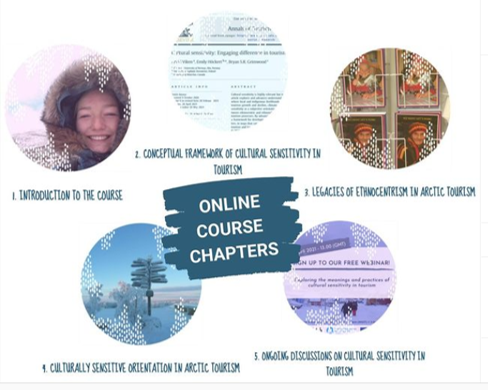

ARCTISEN online courses

*ARCTISEN has aimed to increase this awareness through, among others, producing two online courses about the practical and theoretical implications of cultural sensitivity. Moreover, to include tourists in this process, there is a mini course on its way specially created to make tourists mindful of possible sensitivities at the places and communities they visit.

→ Visit the Department’s

→ Visit the Department’s  → Visit Long Ago People´s Place

→ Visit Long Ago People´s Place  → Visit Tundra North Tours

→ Visit Tundra North Tours